Delivered 5th July 2025 Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, which is showing One Self: The Creative Life of Colin Self until 21st Sept 2025

Playlist:

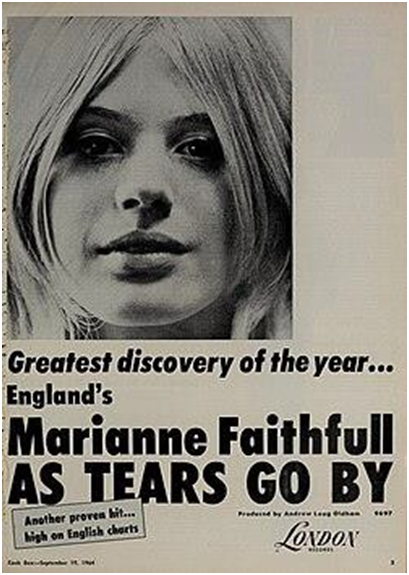

As Tears Go By (June 1964)

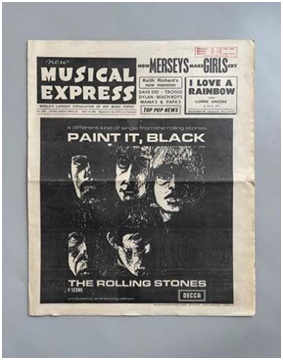

Paint It Black (May 1966)

Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (May 1967)

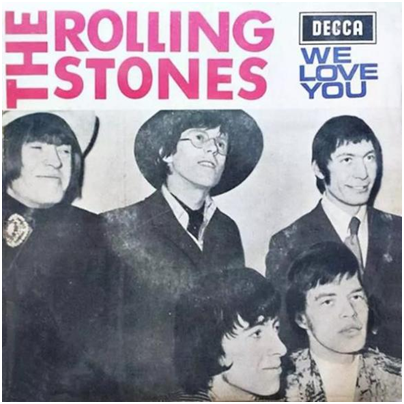

We Love You (August 1967)

I Want To Hang Out With Ed Ruscha (2000)

Eve Of Destruction (July 1965)

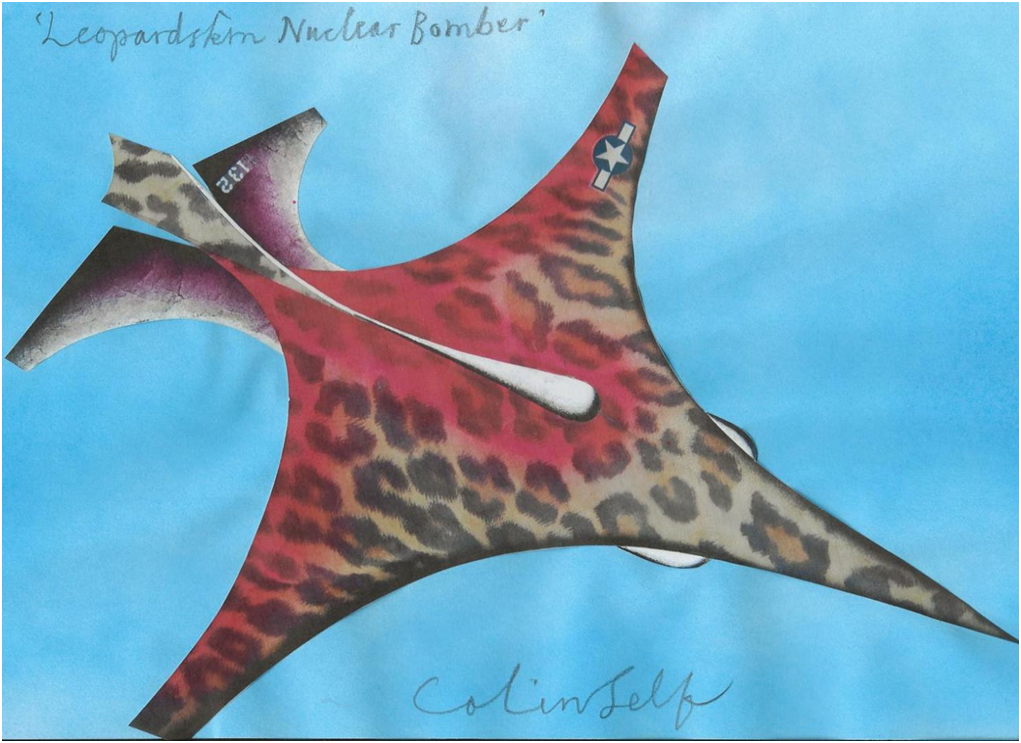

Leopardskin Nuclear Bomber (2019)

As a taster for this essay listen to Marianne Faithfull’s ‘As Tears Go By’ which was in the pop charts in June 1964 & written by Mick Jagger & Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones & their manager Andrew Loog Oldham.

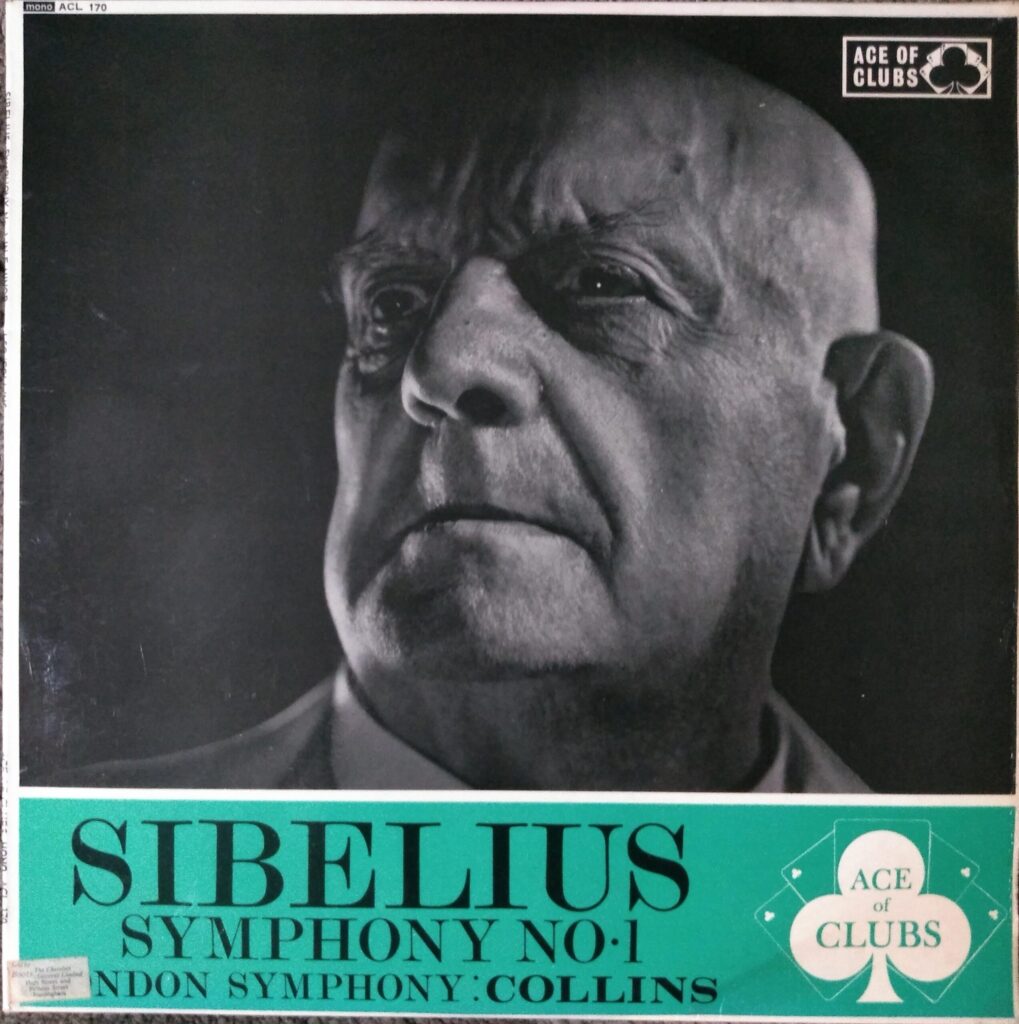

Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones would see Colin’s work, especially his sculptural installations, which were often painted black. More on this later, but now you can see why I listed ‘Paint It Black’ (May 1966) in the playlist above.

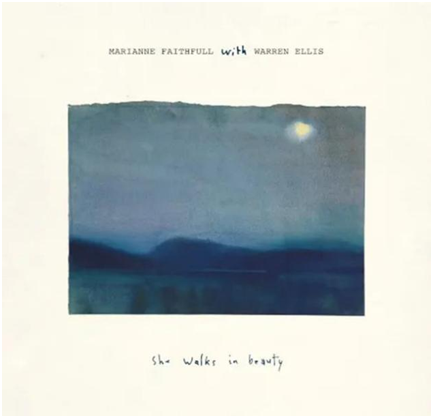

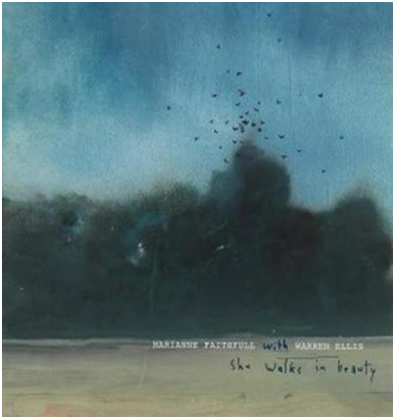

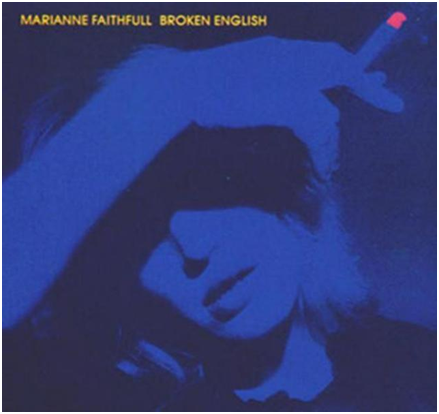

Marianne Faithfull had met John Dunbar in 1963 (& would marry him in May 1965). Marianne & John would become friends with Colin Self. I believe that both Faithfull & Self are true artists, though obviously in different fields. They both have unfailingly pursued their own path & both created powerful, lasting work, always staying relevant – staying true to Sixties ideals, but never stuck in that time. Marianne’s last album (she died in January this year, 2025) was ‘She Walks In Beauty’ in 2021 & she chose paintings by Colin to produce a wonderful sleeve & booklet.

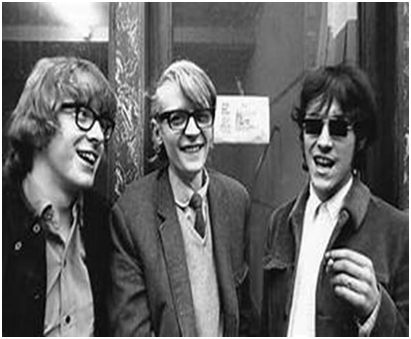

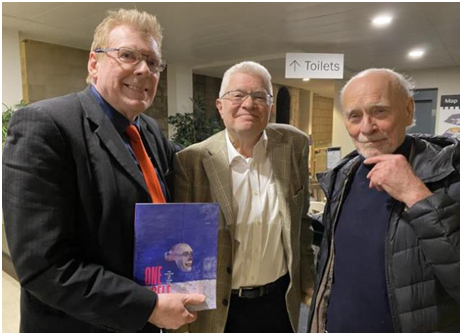

John Dunbar in September 1965 would open an Art Gallery & Bookshop with Barry Miles & Peter Asher, combining their ideas into a company called Miles, Asher & Dunbar Limited (M.A.D.) and naming the gallery Indica (after Cannabis Indica). Below on the left we see Asher, Miles & Dunbar and on the right – at the opening of ‘One Self’ (on Friday 28th March) – myself, with Marco Livingstone [he wrote the Foreword for the ‘One Self’ catalogue and has written extensively about Colin] and John Dunbar, kindly taken by Giorgia Bottinelli (Curator of ‘One Self’ and the instigator of this talk).

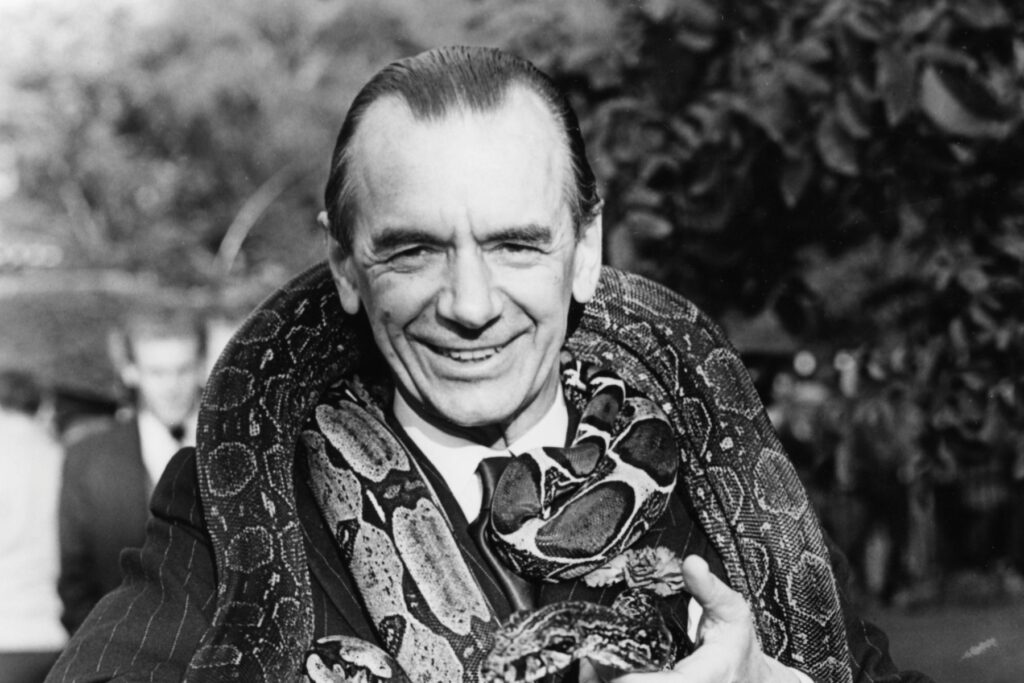

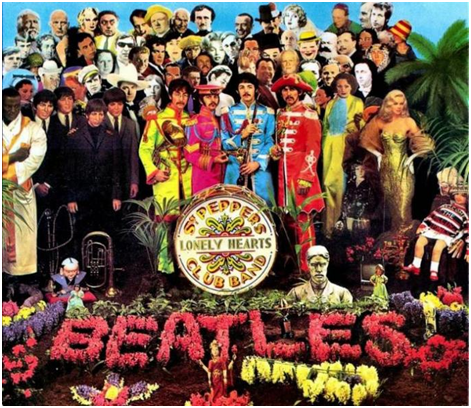

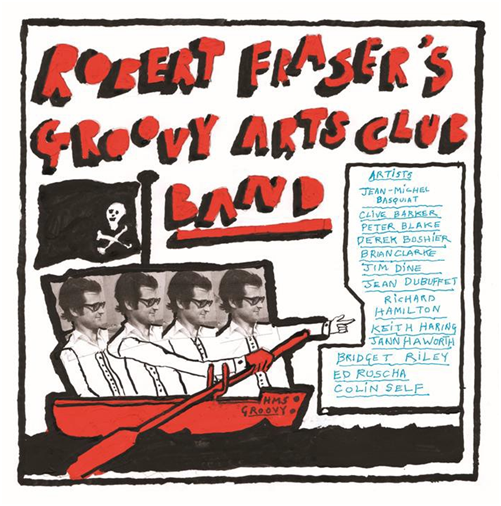

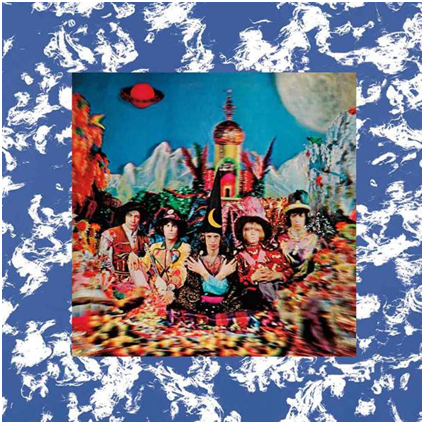

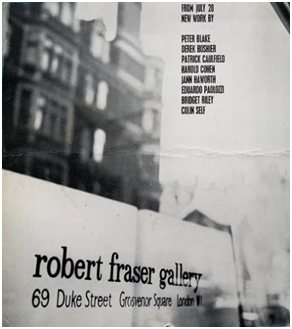

Colin did not become an Indica artist. Later he became part of Robert Fraser’s gallery or what I like to call Robert Fraser’s Groovy Arts Club Band. This is my pun on ( Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band ) two of Robert’s artists were Peter Blake & Jann Haworth. Robert Fraser persuaded The Beatles to discard the intended cover for Sgt Pepper & commission Blake & Haworth to produce their now famous cover.

Robert Fraser was arrested with Mick Jagger & Keith Richards in February 1967. Sentencing happened in June. If you listen to ‘We Love You’, which the Stones released in August of 1967 it has sound effects of clanking prison doors and the official video shows the whole story.

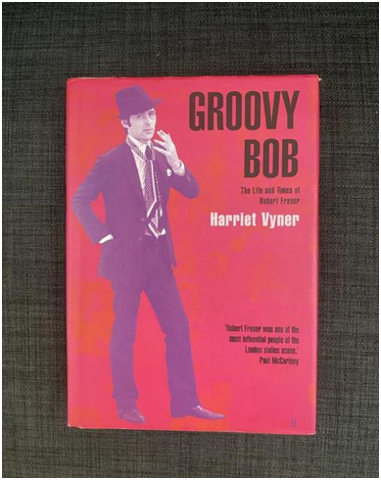

And the next song we hear is ‘I Want To Hang Out With Ed Ruscha’, a slightly more modern recording, having come out in 2000. It is a recording by me and musician/producer Richard Bell & it was the first of my series of songs about visual artists. A few years later I discovered Harriet Vyner’s 1999 book Groovy Bob, all about Robert Fraser & his gallery (incidentally, Marianne Faithful said: ‘Anyone interested in the Sixties should read this book’). Through Vyner’s book I realised that Ed Ruscha had shown at Fraser’s gallery (Duke St, Mayfair, W1 not the Duke St, St James) & then through meeting her, I heard much about Colin Self & many other artists Fraser promoted.

The photograph below is of me with Harriet in Sir Brian Clarke’s studio in 2017, when my band The Groovy Arts Club Band filmed a video in his studio. Brian, who sadly died a few days ago on 1st July, was great friends with Fraser and would often be exhibited in his gallery. It was the seeds of an album, a double-vinyl album in fact, produced, recorded and mixed by Josh Stapleton, celebrating all these fantastic artists, not least, Colin Self.

Colin seems to lead us out of the Fifties into the Sixties and then anticipates the 1970s. The historical period 1958-74 has been described by Arthur Marwick as ‘the long sixties’, a period which can be subdivided into a prelude which lasted until 1963, the stereotyped ‘swinging sixties’ or ‘high sixties’ which lasted until 1968, followed by an aftermath during which the cults and enthusiasms of the earlier periods were widely disseminated and accepted. The ‘long sixties’ends with the economic problems associated with the oil crisis and a widely perceived mood of disillusionment and entropy. I would describe Colin as something of a cool prophet. He certainly anticipates in his art and his statements this disillusionment and entropy. This wonderful retrospective exhibition in Colin’s beloved county of Norfolk is especially pleasing as prophets are not always welcome in their own land! I will talk much more about Colin’s nuclear anxiety and his part in the Swinging Sixties.

The last song we heard was ‘Eve Of Destruction’ (Barry McQuire; written by singer-songwriter P.F. Sloan), but this record came out two years after Colin started producing his bomber prints & sculptures.

‘Leopardskin Nuclear Bomber’ [lyrics by me & music by Derek Jones, who also created the wonderful trousers, which I have brought with me today] features on the album, along with ‘I Want To Hang Out With Ed Ruscha’ and ‘An Englishman In L.A.’, which celebrates artist Derek Boshier (who died 5th September 2024).

Boshier created the sleeve for the double-vinyl album ‘Robert Fraser’s Groovy Arts Club Band’, which was launched in January 2019 alongside an exhibition of the same name that I co-curated with Mila Askorova, at her Gazelli Art House in Dover Street, Mayfair, London.

In the memoir/catalogue, I wrote of the show:

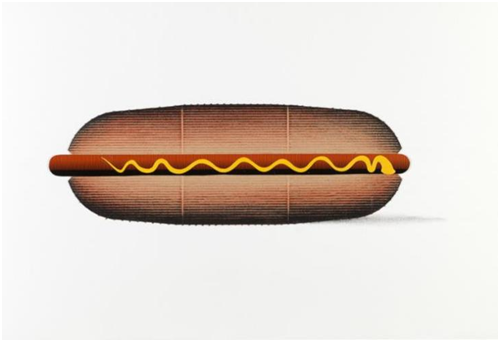

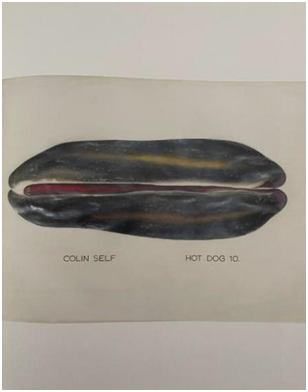

‘the ‘groovy/funky lounge’ section (with electronic wall-screen showing videos of five of the songs from the album Robert Fraser’s Groovy Arts Club Band) drew you in with welcoming chairs, striking Keith Haring wallpaper and treasure trove cabinets (with Fraser ephemera, lent by Harriet Vyner; books signed by Ed Ruscha; the sleeve of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band). On the ‘coffee table’ there were Pop Art and Music books to flick, trawl and wade through. On the surrounding walls, three striking silkscreens by Sir Peter Blake of Bridget Bardot, The Beatles and Kate Moss. Opposite these, Colin Self’s funky and beautifully-realised (and almost edible!) series of mixed media Hot Dogs’.

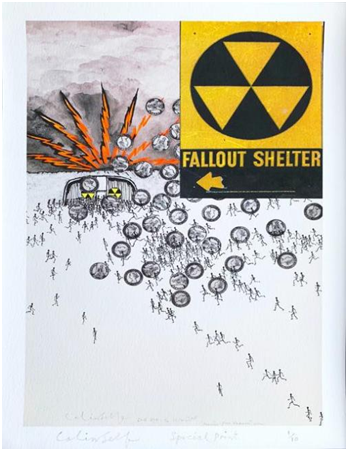

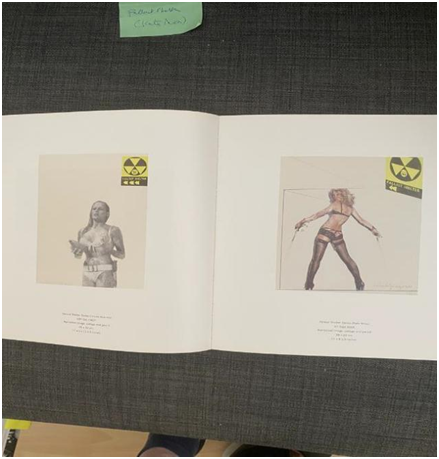

In the display cabinet, we also had one of Colin’s Fallout Shelter artworks and I will be coming back to these as I believe they can also be seen as representing the fallout from the 1960s party/explosion/swinging times.

In these next three slides we see the work of the artists who were in the show at Gazelli Art House: Bridget Riley; Derek Boshier; Jean Dubuffet; Brian Clarke; Clive Barker; Peter Blake; Jann Haworth.

But in the Gazelli exhibition we didn’t have Colin’s wonderful 1965 Hot Dog (painted black, of course!) that graces this Norwich exhibition. And I am delighted that one of the fridge magnets for sale in the shop is Colin’s 2009 Hot Dog, in more edible colours than black! This is what Colin says in Giorgia Bottinelli’s excellent catalogue for this exhibition:

‘To me a hot-dog is as important a 20th century development as (say) a rocket. Both reflect a stage reached; products of our condition.

In the Sixties, I created a series of Hot-Dog drawings. Believing them to be a contemporary fast food/junk food logical progression to the food still lives of Chardin. I thought such thoughts I had then were original. But, being bought a Warhol book as a 50th birthday present, I discovered therein a sketch watercolour of a Hot-Dog (circa 1957/58)’.

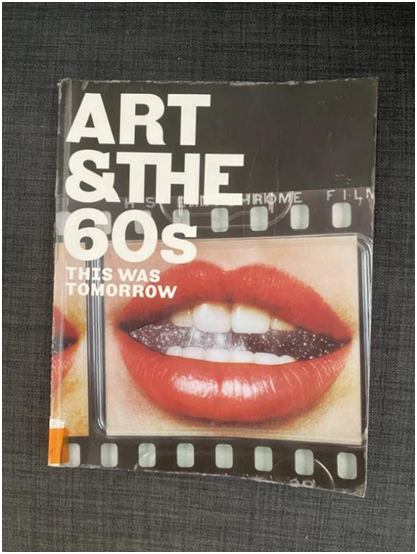

But when it comes to Atomic bombs & bomber jets, Colin gets there first; Andy Warhol’s Atomic Explosion is 1965. The catalogue for ART & THE 60s: This Was Tomorrow – Tate Britain’s impressive 2004 exhibition – includes a section by Ben Tufnell entitled ‘Colin Self And The Bomb’. Tufnell sets the scene for us:

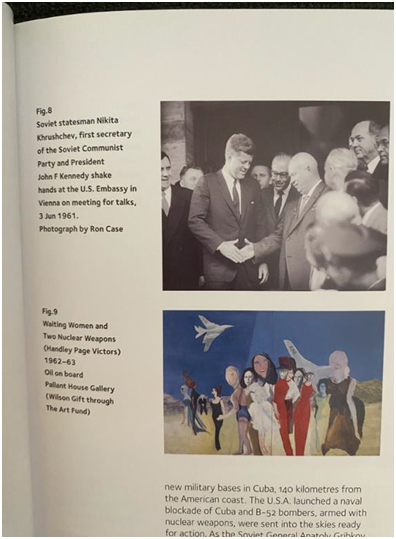

‘17th February 1958 saw the first meeting of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) at Central Hall, Westminster. This was followed at Easter by the first of the annual peace marches to the Atomic Weapons Establishment at Aldermarston. CND grew quickly… at Easter 1960, 100,000 demonstrators gathered in Trafalgar Square. In 1962 the worst fears of the protestors were almost realised as the Cold War entered its most terrifying phase. On 22nd October, President Kennedy announced that Soviet nuclear missiles had been discovered on Cuba, just ninety miles off the coast of Florida, provoking a diplomatic crisis. After a tense face-off during which Cuba was blockaded, the situation was resolved by Soviet Union leader Khrushchev’s undertaking to decommission the missiles, and a reciprocal agreement by the Americans to withdraw missiles from Turkey.’

Tufnell goes on the explain:

‘Given this context it is perhaps surprising how little nuclear imagery appears in the art of the period. Sexuality, civil rights, Cuba, the Vietnam War and other issues appear in work by Hockney, Hamilton, Kitaj & Tilson, but the nuclear threat is conspicuous for its absence. One possible explanation is that the bomb was perceived asAmerican and many of the British artists aligned with Pop Art were engaged with a celebration of American culture. Richard Hamilton [& we have seen his quote on Colin: ‘the best draughtsman in England since William Blake’] – (Hamilton) a committed protestor who was arrested at the CND Holy Loch ‘sit down’ protest in 1961, resolved this personal conflict of interests by reportedly marching with a life- size cut-out of Marilyn Monroe.’

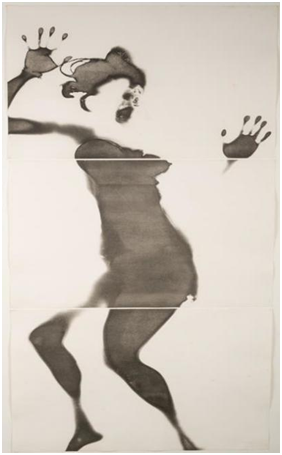

Monroe died in 1962 (the Sixties Prelude). If Colin has ever come close to presenting glamour models, it is always with dark forebodings [as in 1963’s Two Waiting Women and B-52 Nuclear Bomber above], or models with Fall-Out Shelters, or as if just leaving an obliterated nuclear shadow behind [as in 1971’s Prelude to 1000 Temporary Objects of our Times No.7 (Nude Triptych) and shades of Edvard Munch’s The Scream] or as a charred, blackened corpse of a glamour model, 1966’s Beach Girl Nuclear Victim,

which Simon Martin expounds on in the ‘Colin Self: Art In The Nuclear Age’ catalogue, informing us that:

‘Although Self’s Beach Girl has suggestions of Nevile Shute’s 1959 novel On The Beach, which chronicled the extinction of the human race by radioactive fallout in the months following a massive nuclear war, his ideas for the sculpture are first recorded in the sketchbook of his trip to the U.S.A. in summer 1965. Self often noted down his ideas for artworks on which to work when he returned to Britain; his notes read: ‘California girl on beach dead from fallout, with bikini on or part on. With rockets over the top or near figure…. Revolving head (like in hairdresser windows). Head half normal and half like Hiroshima with expensive capitalist wig on.’

The figure was based on a sunbather that the artist saw when he was on the beach in Santa Monica, California, with David Hockney, Patrick Procktor and Norman Stevens. On seeing a heavily suntanned female, Colin exclaimed: ‘There’s my victim!’ and asked her if he could take some photographs for reference. These photographs, together with his drawings of Hiroshima victims, provided the source material for this sculpture, which was based on a shop-dresser’s dummy. It was a controversial exhibit at the Robert Fraser Gallery in 1966. Long after this exhibition Colin sold it to his friends the artist Clive Barker and the model Jean Shrimpton, who later sold it to the Imperial War Museum.

Back to Ben Tufnell’s section in the ART & THE 60s catalogue:

‘[Colin] Self didn’t read any of Bertrand Russell’s texts that argued against the bomb, such as 1961’s Has Man a Future? Colin was too scared. For the same reason he wasn’t a member of CND and he didn’t go on the marches: the issue seemed too vast to confront directly. Every time he watched television or opened a newspaper it seemed there was something about Russian nuclear tests or further deployments of American missiles. The nuclear threat appeared to be omnipresent. Self says: ‘It was as if there was nowhere to hide’.

Unable to speak to anyone about his fears, he experienced what he calls ‘a kind of psychological shut-down’ that only lifted when Kennedy and Khrushchev exchanged peace documents after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Colin says this moment of hope ‘acted like a drop of oil on a machine that was seized up’, and afterwards he began to address the subject directly’.

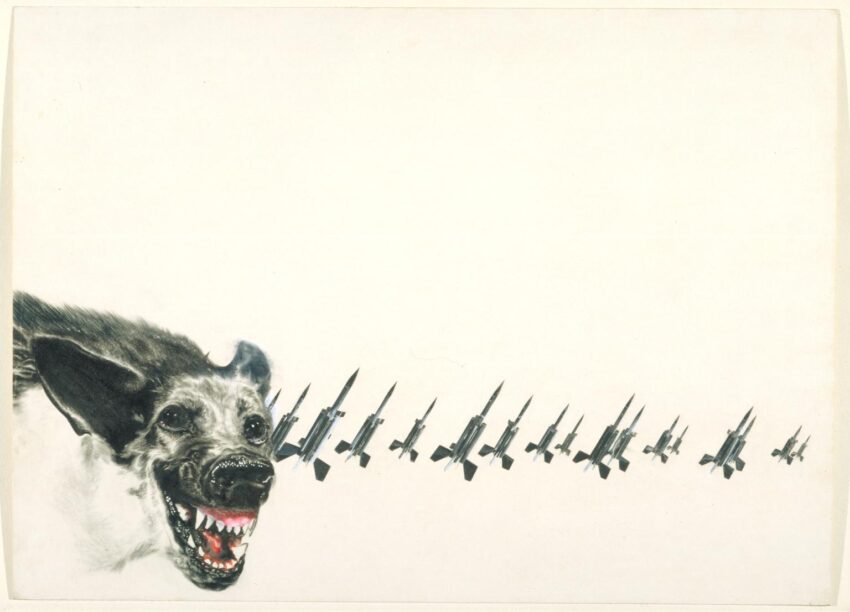

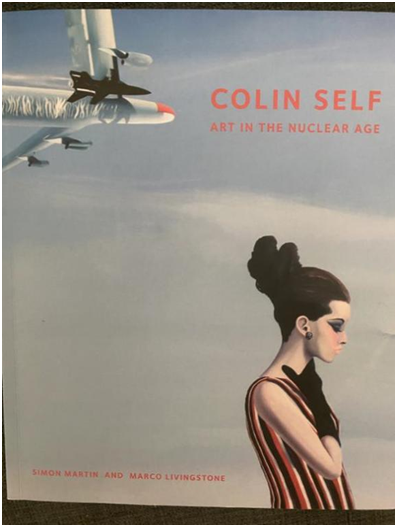

Again, in the catalogue ‘Colin Self: Art In The Nuclear Age’, which was for the 2008 exhibition at Pallant House, Chichester, its curator Simon Martin (who also wrote the catalogue essay ‘Art on the Eve of Destruction: Colin Self and the Nuclear Age’) delves deeply into Colin’s Guard Dogs On Missile Bases in the ‘Catalogue Entries’ section. Martin points out:

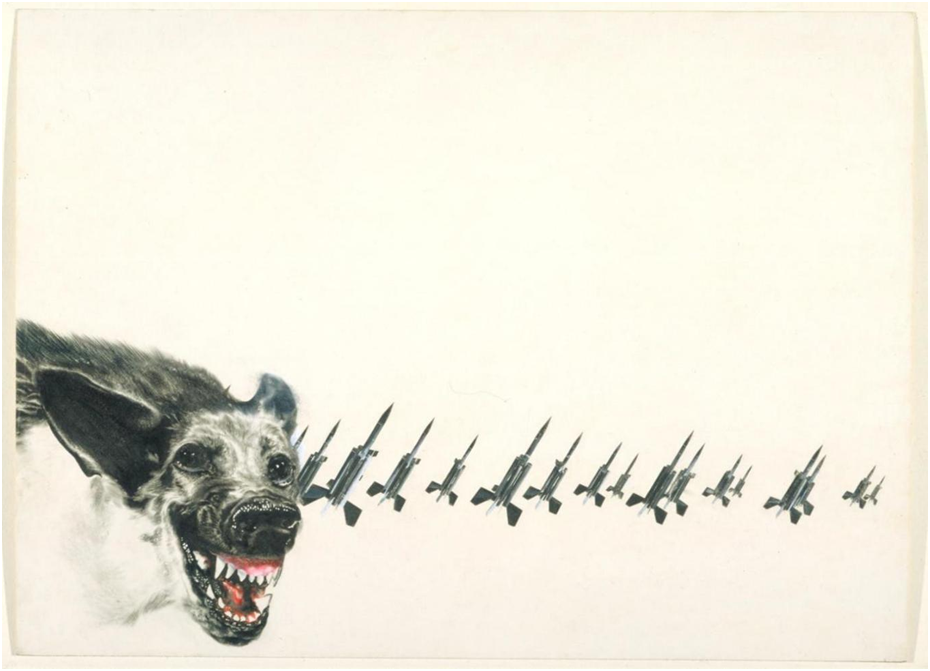

‘From the late 1950s onwards, American nuclear missiles were deployed at a number of airbases in East Anglia, the first of which was in 1958 at Lakenheath in Suffolk. In the summer of 1959, Self was staying with friends on a farm next to the American base at Brandon in West Norfolk, where he was shocked to see a huge Thor Intercontinental Ballistic Missile pointing skywards, Colin describing it as ‘like a nuclear Nelson’s column’. The farm bordered onto the perimeters of the base and at night, Colin was ‘woken by the baying guard dogs, howling at the moon like wolves’. This, and the memory of a traumatic childhood experience, when an Alsatian dog jumped up to sniff him while he was strapped into a pram, were married together to inspire a group of drawings of fearsome guard dogs on nuclear bases that conflated the aggression of the Cold War with animal savage power.

In 1966-67 Colin produced a diorama sculpture, Guard Dog on a Nuclear Base, which featured a stuffed dingo dog before an array of missiles that pointed out towards the viewer through a Perspex screen. It was shown at the Robert Fraser Gallery in 1967, where Colin says: ‘it was much admired by Francis Bacon, who later took Frank Auerbach to see it. Bacon exclaiming: ‘Each time I come back it gets better and better’. Sadly, the artwork has since been destroyed. Brian Jones would have seen this diorama and in some notes that Colin & his wife Jessica sent me the other day, Colin confirms that Brian Jones bought a Guard Dog On A Missile Base drawing.

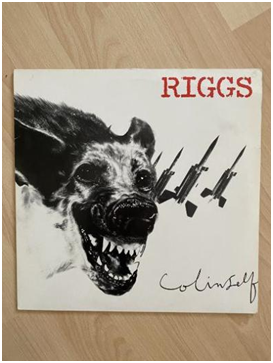

Guard Dog on A Missile Base [10th March 1966, Pencil, collage & spray-paint on paper; now in the Imperial War Museum] was used very effectively for the sleeve of a 1982 album by USA hard rock band Riggs (led by lead guitarist Jerry Riggs); Colin is credited as ‘Colin Self of Norwich’. And while we are on album sleeves, perhaps the most famous album sleeve ever is Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which we have already mentioned earlier. The photographer who took the photographs of Blake & Haworth’s Sgt Pepper installation was Michael Cooper, who in 1966 superimposed Colin Self’s head onto the Guard Dog, calling it Bloodhound Missiles and Guard Dog. I have now superimposed David Bailey’s photograph of Michael Cooper on my slide!

With all this talk of missile bases and nuclear bombs, we have to turn our attention to director Stanley Kubrick’s film (released January 1964) Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb – a painfully funny take on Cold War anxiety now known as one of the fiercest satires of human folly ever to come out of Hollywood. And like Colin Self’s black sculptures, a black-and-white film; an appropriately black comedy. But we know that Colin has certainly not learned to love the bomb!

This film had a huge impact and influence on so many people; it has to be one of the defining films of the Sixties. Colin says that: the nuclear message in the film – was the world going to survive it? – was very much his inner thought and something he expressed in his art many times. Colin also notes that Terry Southern (scriptwriter on Dr Strangelove) bought Colin’s Missile Painted Black sculpture from Robert Fraser; but it disappeared and never reached Terry Southern in the U.S.A! In his recent notes to me, John Dunbar says: ‘I nearly worked on Dr Strangelove; it’s a great movie’. In fact, it is still as funny and razor- sharp today as it was in 1964. John Patterson in The Guardian has written: ’There had been nothing in comedy like Dr Strangelove ever before. All the gods before whom the America of the stolid, paranoid 50s had genuflected—the Bomb, the Pentagon, the National Security State, the President himself, Texan masculinity and the alleged Commie menace of water-fluoridation—went into the wood-chipper and never got the same respect ever again’. The film starts with these words on the screen:

‘It is the stated position of the U.S. Air Force that their safeguards would prevent the occurrence of such events as are depicted in this film. Furthermore, it should be noted that none of the characters portrayed in this film are meant to represent any real persons living or dead.’

Peter Sellers gives an incredible performance, playing no less than three characters: Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, a British RAF exchange officer; Merkin Muffley, President of the U.S.A. and Dr Strangelove, a wheelchair-bound nuclear war expert and former

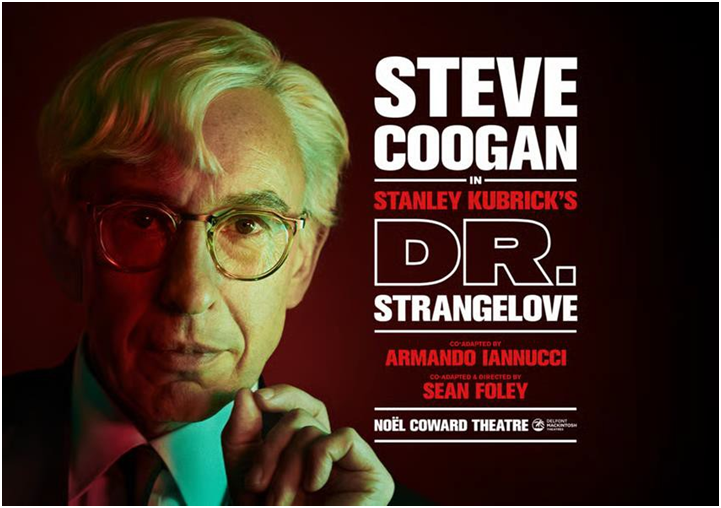

Nazi, who has alien hand syndrome. Steve Coogan recently starred in a National Theatre production of Dr Strangelove; Coogan playing not just three characters, but four!

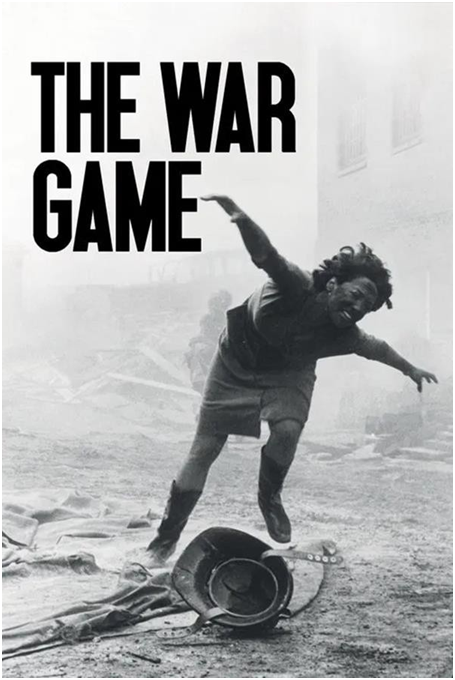

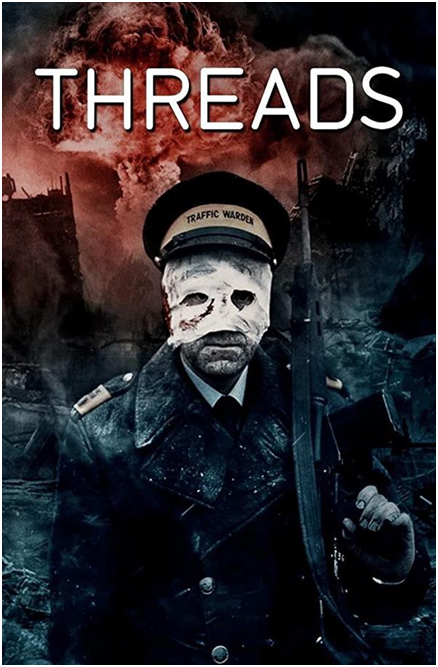

We need to also mention the film ‘The War Game’ (directed by Peter Watkins), a pseudo-documentary that depicts nuclear war and its aftermath. It was released into film theatres in April 1966. The War Game only saw its broadcast on television in the United Kingdom on BBC2 on 31st July 1985, as part of a special season of programming entitled After the Bomb (which had been Watkins’s original working title for The War Game). After the Bomb commemorated the 40th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The broadcast was preceded by an introduction from Ludovic Kennedy.

This was just a year after the Mick Jackson film ‘Threads’ was televised; a film which dramatizes the fall-out from a nuclear attack on Sheffield with harrowing realism. It was shown again in 2024 to celebrate its 40th anniversary. As well as despairing at the premise of these films, you cannot help thinking also of Colin Self’s artworks inspired by the threat of nuclear war and the proliferation of nuclear missile bases. And this is still, unfortunately, very much a reality today.

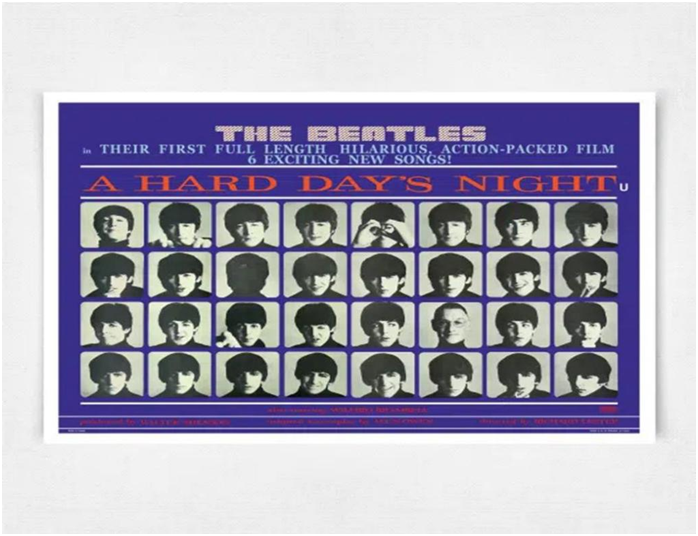

I think it is time for us to move away from the dark side and the noirish preoccupations of the Sixties and go for something more joyous. Let’s consider another black-and-white film released (in July 1964) six months after ‘Dr Strangelove’. Yes, we are talking about the Fab Four. We are talking about ‘A Hard Day’s Night’, directed by Richard Lester.

A musical comedy film of 36 hours in the lives of The Beatles, along with the wonderful actor Wilfred Brambell.

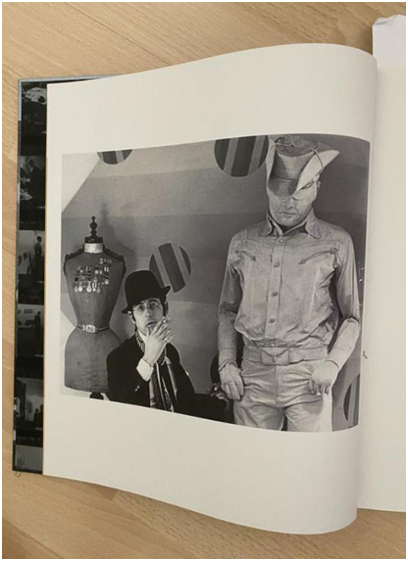

Like the best things from the Sixties, this film is timeless. Rotten Tomatoes says: ‘A Hard Day’s Night, despite its age, is still a delight to watch and has proven itself to be a rock-and-roll movie classic.’ It is a subtle satire on Beatlemania, the Beatles themselves, along with the world teenage exploitation and fashionable ad agencies. In fact, in this scene we glimpse a Colin Self artwork (Colin says it is ‘a bomber’ wing’);

Recently Colin explained to me: ’Slade friends Jo Keyes and Terry Atkinson went to Shepperton Studios with our artworks for the film. Jo took a photo from an upper window of George Harrison walking across to the studio. I have this photograph somewhere’.

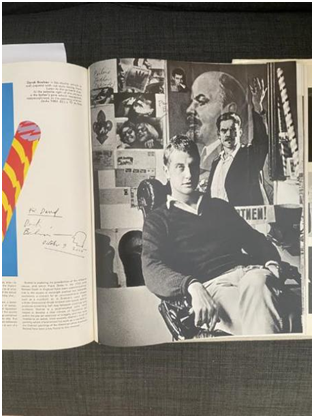

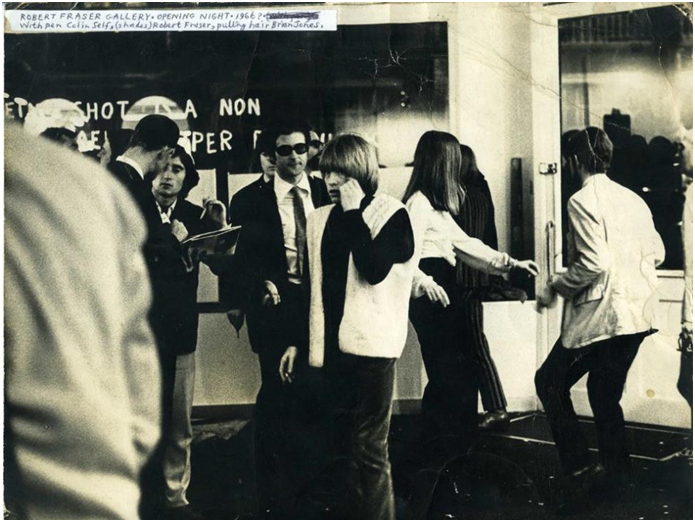

So after all the nuclear doom this is when we can cheer Colin and ourselves up! Because in 1965 Colin meets a flamboyant and exciting character called Robert Fraser, who knew the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, who all frequented his remarkable art gallery. Let’s have a closer look at this photograph:

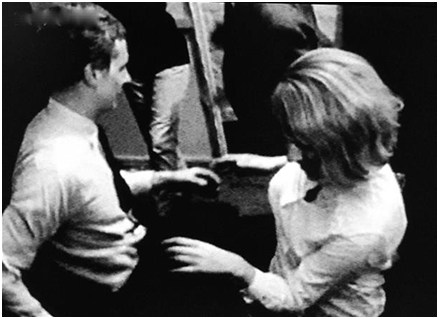

This is why I asked for it to be included in the publicity for this talk and I am delighted it is part of this wonderful Colin Self exhibition. The photograph is of an exhibition launch at the Robert Fraser Gallery (most probably in 1966); we have Colin (with pen) on the left looking very groovy; next to him Fraser himself – ‘Groovy Bob’ looking impossibly cool in his shades and tie. Then we see Brian Jones who looks like he’s on a mobile phone, but he is obviously not (must be fiddling with his hair). Perhaps he is looking at one of Colin’s black sculptures. Colin has pointed out to me that: ‘Brian Jones was very shy; we only used to exchange a few sentences’. The Rolling Stones ‘Paint It Black was recorded in March 1966 & released in May. Brian was never a songwriter but I do feel he would have shared ideas for songs as well as his inventive musicianship with Jagger & Richards. Thus ‘Paint It Black’ could very well be inspired by Colin’s work.

And then we have a couple dancing; looking like they might be doing the Twist. I am reminded of the 1962 BBC TV Programme Pop Goes The Easel, a documentary, directed by Ken Russell, about four ‘Pop artists’: Peter Blake, Pauline Boty, Derek Boshier & Peter Phillips (who died just very recently on 23rd June 2025).

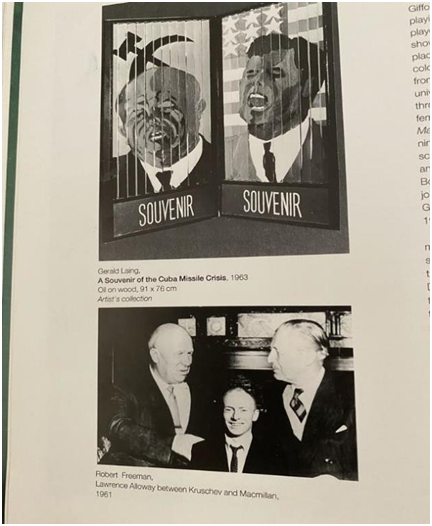

The photograph really does seem to sum up ‘swinging sixties’ or ‘high sixties’; and it is taken by a very important photographer Robert Freeman. And guess what, his photographs of the Beatles were used for ‘A Hard’s Days Night’ film poster and the soundtrack album, the third Beatles album and the second Freeman photographed for – his photographs were also used for ‘With The Beatles’, ‘Beatles For Sale’, ‘Help’ (that other great rock and roll movie of the Sixties) and ‘Rubber Soul’. He wanted ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ cover to suggest the idea of movement, by expressing a flow of a picture: four rows of four head shots, set up as though they were frames from a movie. The pictures of the four individual Beatles were taken in Freeman’s studio. He first met The Beatles in the summer of 1963; he had already established a reputation through The Sunday Times magazine. He says: ‘ I’d recently been on assignment in Moscow to photograph Khrushchev in the Kremlin and earlier that year had shot the first Pirelli calendar.’

Freeman also liked to sometimes manipulate photographs, as we can see in this 1961 photograph (above): he has placed the art critic Lawrence Alloway between Kruschchev and Britain’s Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963, Harold Macmillan. By the way, Alloway (who died in 1990) is an important figure. He was an English art critic and curator who worked in the United States from 1961. In the 1950s, he was a leading member of the Independent Group in the UK and in the 1960s was an influential writer and curator in the US. He first used the term “mass popular art” in the mid-1950s and used the term “Pop Art” in the 1960s to indicate that art has a basis in the popular culture of its day and takes from it a faith in the power of images.

And it is Pop Art that Robert Fraser often promoted in his gallery.

American artist Jim Dine says of him:

‘Robert was the hippest person I ever met. Every night at 23 Mount Steet [Fraser’s flat in Mayfair] there was some pop star, movie star, artist, whatever. You couldn’t keep up with that. You just had to be yourself, because you couldn’t make it up.’

In Harriet Vyner’s book, Colin recounts meeting Fraser in 1965: ‘The first time I ever met Robert was when he came to my house at 25 Tivoli Road in Hornsey. I was working on the Victor Valiant nuclear bomber, the Handley-Page Victor Bomber with missiles on, which Terry Southern [the writer who helped script Dr Strangelove] then later bought, and Robert took one look and said, ‘I want that in my summer show’.

He smelt quite nice, very presentable, in a pink shirt, stuttering a bit, a bit nervous, then the stuttering lessened as he got more comfy with us, and he wanted to represent me. I said, ‘Well, yeah, I’m interested, I’ll put the sculpture in.’ After that I switched from the Piccadilly Gallery to Robert.

I must mention Robert’s belief that I am a great artist. I really must confirm that. I think he really, really did think I was special. It’s nice to have someone believing in you. He wasn’t a good-time Charlie or a crook, he was such an entrepreneur, a bit like Diaghilev, who was a bit of a cheat and left people stranded, but put on great shows.’

In the foreword of the catalogue for the Mayor Gallery’s Colin Self: Streetseen, Hearts and Glances (25th Nov to 18th Dec 2015) exhibition, Colin expounds:

‘Being a keen footballer and left-handed I was put on the left wing and learned to use my left foot. So it all leads to awkward practical situations from which one develops an advanced skilled learning of how to innovate and compromise. One becomes an ‘awkward individual’ in the majority right-handed society’s world. Or? Are we left handers out of touch with planetary movement itself? Robert Fraser was extreme left-handed too and thus we understood each other.’

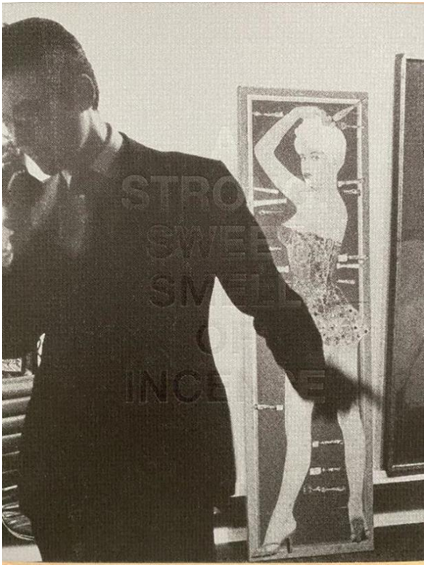

Colin Self was, not surprisingly, included in the February/March 2015 exhibition A Strong Sweet Smell Of Incense: A Portrait of Robert Fraser at Pace Gallery, Burlington Gardens, London W1. Works shown were Oblique Head In A Sterile Landscape (1964; Painted fibreglass and aluminium) and Hot Dog (1965; Pencil & Watercolour on paper), which looks anything but edible!

In the catalogue, curators of the show, artist Brian Clarke [BC; Brian, now Sir Brian Clarke, sadly died just four days ago on 1st July 2025] & writer Harriet Vyner [HV] expand on Fraser and Colin’s association and the groovy world of the Robert Fraser Gallery:

‘HV: Richard [Hamilton] told me that Robert’s gallery was the best of the post-war years – unique and marvellous. And it was he who suggested Robert look at Colin Self’s works. [I must interject here with John Dunbar’s recent words to me: ‘When Colin came into Indica gallery, I suggested that Robert Fraser Gallery would be more appropriate and I introduced Colin to Robert, where he did show’.] Robert visited Colin on the way back from seeing Richard and found him working on the Victor Valiant Bomber that Terry Southern later bought. He signed him up at once. Colin remembered that Robert smelled very nice.

I didn’t know much about Colin when I went to interview him. But as soon as I met him, I was thrilled. I felt that there should be a book about him, working in this modest house in Norfolk filled with a jumble of his odd and diverse masterpieces. At one point, I told him that you [Brian Clarke] admired his work, and after the meeting he sent both you and me that lovely picture of Mickey and Minnie in bed.

BC: Which I truly treasure. Colin was a mysterious figure to me. He was not one of those people who was out there as a recognisable face. But he was always there as a very powerful artist. And anyone who knows anything about British Pop Art regards him as a genius. Robert certainly did. When he spoke about Colin, it was in a way that he didn’t speak about other artists. He could make jokes about him, as he did about everyone, but as far as Robert was concerned – he knew. I think of Colin Self as an artist whom the world hasn’t f-ed up or corrupted. The world has essentially ignored a luminous creative talent. And it will be sorted out eventually, no doubt about it. He’s very special.

HV: Derek Boshier told me about lying on a Malibu beach with David Hockney and Colin in the early 1960s, staring at the sky and trying not to feel too pasty and English, while all around them the beautiful Californian youth were leaping around and swimming. Suddenly they heard Colin announce: ‘I’ve got a great idea for a sculpture – it would be a life-sized female body charred black by a nuclear bomb blast.’

BC: Makes you proud to be British!

HV: It does. And this very work features in David Bailey’s photograph of Robert in the gallery. Dean Stockwell is one of those friends.’

I love this beautifully-composed and quite wonderful 1968 photograph by David Bailey. t seems to be so utterly ‘Sixties’. Would be great if Colin himself was in it, but his 1966 Beach Girl Nuclear Victim most certainly is, placed dramatically in the foreground. As well as Robert Fraser, who is in the centre we can recognise Jann Haworth in the white coat. We know that American actor Dean Stockwell is one of the other three ‘living’ figures and he is at the back to the left of Haworth. Further research has revealed that on the right is Tony Sanchez (‘Spanish Tony’), drugs dealer for the Rolling Stones and author of Up And Down With The Rolling Stones. And sitting on the floor is jewellery maker David Courts, who attended the ‘One Self’ launch evening back in March this year (2025).

Vyner’s Groovy Bob has a Prologue by Mick Jagger; he writes:

‘… so if you’re talking about the sixties, Robert was in a way more like one of those fifties people you see in photographs who used to deal in art or dabble in it then. He was like one of those John Deakin people, with the pinstripes, nice ties, blue Turnbull and Asser shirts, his hair always perfectly combed, always well-shaved and so on, that sort of person. Public school; Eton, you know [Jagger is quite correct; Fraser did attend Eton]. Bit of money. Falls into another world. He wants to be on the edge of the demi-monde – but he’s not happy with the demi-monde. He wants to be on the outside edge, where there’s criminal activity…. He’s gay, but not with a nice hairdresser boyfriend more gay in the rent-boy way – doesn’t want to show he’s gay. He’s a drug addict – doesn’t want to show he’s a drug addict…. But what else is he doing? He’s presenting this new kind of art. Who to?

Well, not so much to gay gentlemen living in the Albany [in Piccadilly, London] on family money, making good investments, but to young upstart people [Jagger is referring to himself & his scene, of course] in this brash new world of England which hadn’t really existed before.’

And it was through Mick Jagger that Fraser become much more widely known (for a little while anyway).

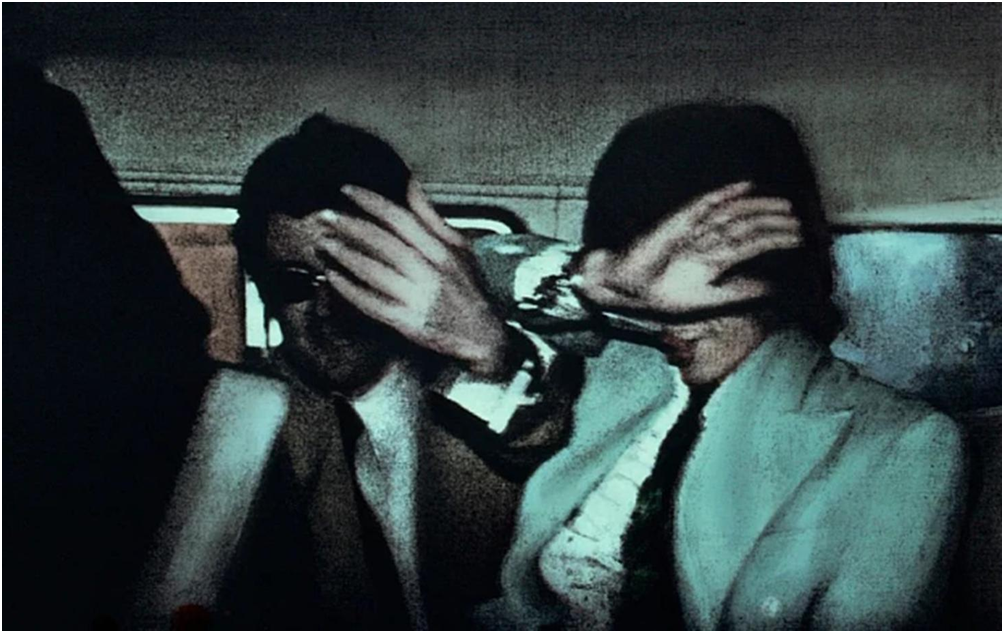

Here is the famous artwork by Richard Hamilton; Fraser handcuffed to Jagger, as they leave Chichester Crown Court on 27th July 1967.

Arrests had been made on 12th February; newspapers reported:

‘Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of rock band the Rolling Stones have appeared before magistrates in Chichester, West Sussex, charged with drug offences.

The magistrates heard that after a tip-off, police raided Mr Richards’s mansion in Redlands Road, West Wittering on the evening of Sunday 12 February during a party. They searched the house, interviewed eight men and one woman [this woman is Marianne Faithfull, who was only wearing a rug, apparently] and found various tablets and substances that were later examined by the Metropolitan Police Laboratory.

During the police raid, officers took away a number of items including Chinese joss sticks suspected of masking the sweet smell of cannabis resin and pudding basins holding cigarette ash.

Stones’ lead singer Mr Jagger, 24, has been accused of illegally possessing four tablets containing amphetamine sulphate and methylamphetamine hydrochloride. Guitarist Mr Richards, also 24, is charged with allowing his house to be used for the purpose of smoking cannabis. Both Mr Jagger and Mr Richards pleaded not guilty and were released on bail to appear for trial at West Sussex Quarter Sessions on 22 June.

Outside the court, a crowd of young fans were waiting to see the stars but the two men were driven away in a chauffeur-driven car from the back of the building. A third man, 29-year-old Robert Fraser, a gallery owner has been charged with possession of heroin and eight capsules of methylamphetamine hydrochloride.’

On 29 June 1967, Jagger was sentenced a £200 fine and to three months’ imprisonment for possession of four amphetamine tablets. Richards was found guilty of allowing cannabis to be smoked on his property and sentenced to one year in prison and a £500 fine. Both Jagger and Richards were imprisoned at that point: Jagger was taken to Brixton Prison in south London and Richards to Wormwood Scrubs Prison in west London. Fraser received a year in Wormwood Scrubs and did not appeal. Both Jagger & Richards were released on bail the next day.

Fraser comes off worse than anybody, but apparently he enjoyed his time in prison. And so for now, we will leave Fraser in Wormwood Scrubs. It seems that the Sixties ‘party’ or, indeed, the ‘high sixties’ is coming to an end, and perhaps needs some kind of metaphorical ‘Fall-Out Shelter’. Sadly, Brian Jones never found it; he became a victim of the Sixties; this is his letter to Fraser in prison:

‘Dear Robert

How’s everything – I hear you are really grooving behind jail. Sorry I haven’t written earlier but I spent a month doing a nursing home scene then I spent a freaky month in Spain. We are busy right now laying down tracks for the LPs [from February to October 1967, they were recording for the album ‘Their Satanic Majesties Request’ (released in December with a sleeve – almost a pastiche of Sgt Pepper & also photographed by Sgt Pepper photographer Michael Cooper) & their single ‘We Love You’, released August 1967.

Written as a message of gratitude to their fans for the public support towards them during the drug arrests of Jagger and Richards, the recording features guest backing vocals by John Lennon and Paul McCartney of the Beatles. It is considered one of the Rolling Stones’ most experimental songs, featuring sound effects, layers of vocal overdubs, and a prominent Mellotron part played by Brian Jones]-

Brian continues his letter: ‘I’m planning to leave on Friday for Tripoli, then dig some oases in the Libyan desert. I hope to be there for a couple of weeks. I hope to find a groovy scene there. Well, look forward to seeing you soon. Lots of love. Brian’

Marianne Faithfull adds a line to Fraser at the bottom of the letter: ‘I’m sure you are well and Tantra is keeping you from all evil spirits. Love Marianne.’

Marianne Faithfull nearly became a casualty of the Sixties, but fortunately she turned out a survivor (though her ‘fallout shelter’ was a wall in Soho for a couple of years from 1970, the year her relationship with Mick Jagger ended). And it was in the 70s that Colin got to know Marianne better, as she still kept in touch with Dunbar, and this was the time when Colin & John Dunbar became good friends. In recent notes to me, Dunbar says: ‘A childhood friend from Pinner had bought a few acres in a beautiful valley in the Scottish uplands. And I took Colin up there in the early 70s; this was after we had made some extraordinary trips to Germany and Norway’. Since Marianne’s remarkable 1979 comeback album ‘Broken English’ she has become, quite rightly, a very respected artiste, collaborating with people like Hal Willner, Steve Winwood, Nick Cave, Warren Ellis and Jarvis Cocker. Sleeve photographer for ‘Broken English’ is Dennis Morris (who photographed Bob Marley & Sex Pistols & is being exhibited at the Photographers’ Gallery, London: June to September 2025 Music + Life). Marianne died in January this year; she always respected Colin and on her last album that Colin illustrated she wrote: ‘Thanks and love to Colin Self’. Colin had never tried to get into bed with Marianne. But in the 1960s particularly, Marianne would be pursued by men (and also women); in his notes to me, John Dunbar mentions a memorable Otis Redding concert, where ‘Otis tried to get off with Marianne’.

What did Colin Self make of it all? His own ‘fallout shelter’ was leaving London to live in Norfolk ( and undoubtedly, those later holidays with Dunbar). He continued to show with Robert Fraser until 1968; the gallery closed in 1969, though Fraser would open a new Gallery in Cork Street, London W1 in the early 1980s, but that is a whole other story – back to Colin, who says:

‘I’ve somewhere got a pile of Robert’s gallery stickers with the odd lettering. Also one of his bounced cheques. Looking back, I treated Robert like family when the setbacks came, as if he was my youngest uncle. If you got ripped off, it was like a family rip-off. I always thought Robert was special.’

From 25th January to 30th March (1967; during the time period of the Redlands bust 12th February), Colin was showing with Clive Barker, Peter Blake, Richard Hamilton and Jann Haworth – esteemed company – at Fraser’s gallery. Day-to-day running of the gallery was handled by Fraser’s very capable assistant Susan Loppert, who wrote this to Fraser in prison:

‘Things at the gallery continue as before, a little more sluggishly perhaps, now that the novelty of the notoriety has worn off, as well as the usual August deadness. Clive [Barker] is getting set to go off to San Marino with Christopher Finch [artist & author; in 1973 he wrote his first book about pop culture The Art of Walt Disney]; Derek [Boshier] is still waiting to hear about the proposed world trip; Jann [Haworth] is preparing madly for her show at Felix Valk [I need to research this name further], which is due to open on the 12th October; Peter [Blake; married to Jann Haworth at this time] is painting away industriously for the Carnegie show; Richard [Hamilton] has just delivered ten each of his Toast Bing Crosby & TIME Self Portrait prints for us to sell; Colin [Self] has found a new method of doing dyelines so that they last.’

1969 saw Colin attend the Rolling Stones Hyde Park concert, exactly 56 years ago, because the concert was on 5th July (& also a Saturday – date of this talk: Saturday 5th July 2025). Colin remembers the white butterflies being released to remember Brian Jones (who had died two days before on 3rd July); here is a photograph of Marianne Faithfull at the concert with her and Dunbar’s son, Nicholas.

Colin had also just signed with Marlborough Fine Arts in London, but soon after decided to represent himself and this is when he chose to settle near Thorpe St Andrew, on the outskirts of Norwich. So throughout the 60s Colin had dealings with some of the top galleries: Kasmin Gallery (David Hockney had introduced Colin to John Kasmin); Piccadilly Gallery; Indica Gallery (run by his good friend John Dunbar); Robert Fraser Gallery & Marlborough Gallery (where Francis Bacon showed).

As Margo Livingstone writes (in his ‘Racing Thoughts’ in the 2008 Art In The Nuclear Age):

‘The urge to label or contain a spirit as free and original as Self’s led him to being regarded as part of the Pop Art movement. Though his attitude to consumer society was often critical rather than celebratory, in terms of his use of popular and contemporary imagery, it was certainly a field with which he felt affinities.’

Colin is very much a survivor, but more to the point – a commentator on and an influencer of the Sixties and since than he has never stopped producing fabulous artworks.

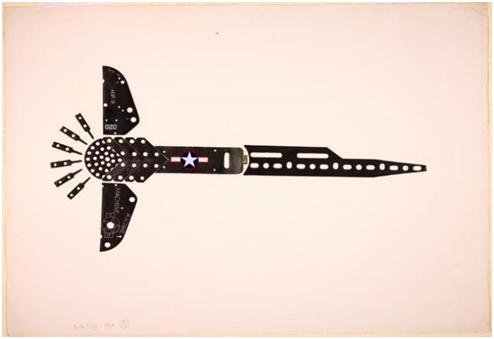

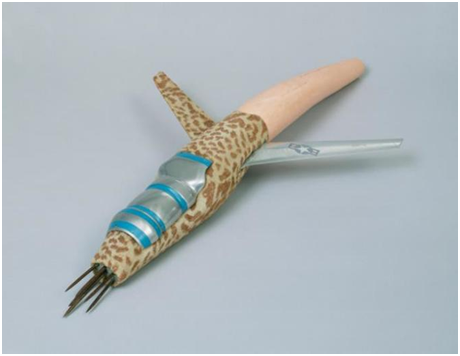

A couple of years ago, Colin very kindly created a Leopardskin

Nuclear Bomber for me; it seems to be very much a combination of his 1962 That’s the Trouble with the Bastards’ and his glorious (if I can really use that word in the context of nuclear bombers!) 1963 (purchased by the Tate in 1994) Leopardskin Nuclear Bomber No.2.

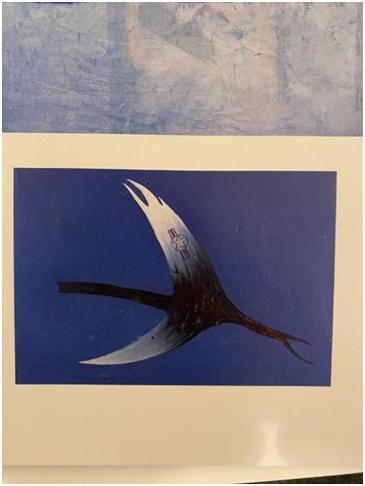

‘That’s the Trouble with the Bastards also relates to Colin Self’s feelings about the nuclear stand-off between the U.S.A. and the

Soviet Union. The strange creature swooping through the skies is a hybrid of a modern F-4 nuclear bomber and a Pterodactyl, a flying reptile of the Mesozoic Era that hunted by swooping on fish. Its beaked mouth is open and its elongated neck bears the eponymous

angry message in red paint like a graffitied slogan. On one wing it has the insignia of the U.S. Air Force. The artist has explained: ‘’The

message could be construed as ‘Watch it!’ This thing could make us all extinct, but we won’t become extinct in the same way that the dinosaurs did. We’ll be masters of our own extinction.’’ Colin saw the Americans and the Soviets as equal aggressors at this time and therefore created a cross-breed.’

I will end with a band new video for the song ‘Leopardskin Nuclear Bomber’ specifically created for us to experience as a culmination of this talk.

David G. A. Stephenson

With thanks to Colin & Jessica Self