What do you need for the perfect Christmas Day? Quick checklist:

- family around you

- a bloody big turkey in the oven

- oceanic quantities of booze

- a shiny new electric train set

- simmering hate-fuck sexual tension between the adults

- a cold blast of existential despair

“Wait, what?” I hear you cry, having reached the last two of those. Since when have simmering hate-fuck sexual tension and existential despair been constituent parts of the essential Yuletide experience? To which I reply: since we decided to spend Christmas with Tom, Cleo and Giles in the unjustly forgotten chiller Eclipse (Simon Perry, 1977).

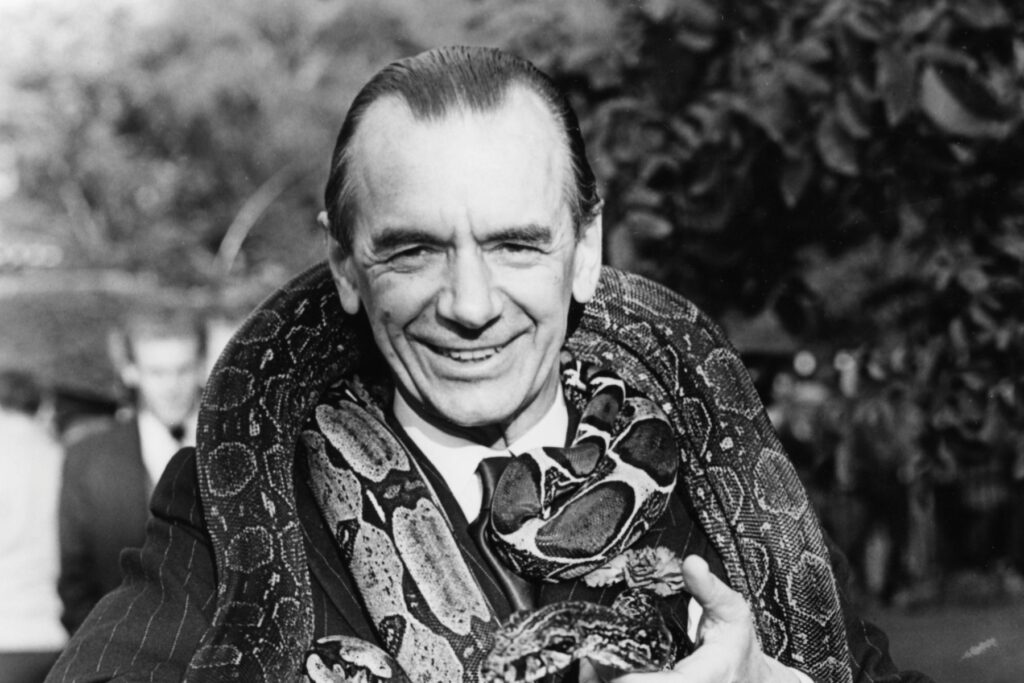

The set-up is simplicity itself: Tom (Tom Conti) and his widowed sister-in-law Cleo (Gay Hamilton) attend an inquest into the death of his brother/her husband Geoffrey (also Conti) following a boating accident after the brothers inadvisedly took their vessel out during a lunar eclipse. Cleo’s behaviour towards Tom is frosty, as is that of the Procurator Fiscal, who clearly has issues with Tom’s testimony but in the absence of any other evidence begrudging records a verdict of death by misadventure. Despite the fraught atmosphere, Cleo asks Tom as they leave the court if he’ll spend Christmas with them – the other party in “them” being her precocious son Giles (Gavin Wallace). Tom accepts, evidently more out of duty than anything else, and Cleo commences the lonely journey back to her isolated home in Caithness in the Scottish highlands. Thus the first quarter of an hour of a 90-minute film; and thus a prevailing aesthetic – visually austere, directorially unshowy, almost documentary-like in its presentation of character, place and incident.

An immediate cut from the conclusion of Cleo’s journey to the lights of Tom’s Land Rover stabbing through the darkness of Christmas Eve as he jounces along the little-used road to chez Cleo shunts the viewer abruptly into the film’s extended second act. And again, the set-up is uncomplicated: Tom rocks up with extravagant gifts for Cleo (a silk evening gown) and Giles (a train set and so many accessories that he probably emptied his local model shop), takes over chef duties for what is intended as a slap up Christmas dinner, discovers that Cleo has an Oliver Reed grade drink problem, incurs her wrath and Giles’s delight when he insists on taking the boat out of Boxing Day, and finally comes to terms with what happened that fateful night of the eclipse.

Right up until the supernatural becomes explicit about eight minutes shy of the end credits, Eclipsetrades on nuance and suggestion in much the same way that The Turn of the Screw and The Haunting of Hill House wring terror from their protagonists’ states of mind, hinting at the things lurking in the shadows rather than actually showing the ghost or monster. Slow burn to the point where you’re not sure than anyone struck a match in the first place, Perry very veeeeery gradually allows a sense of “off-ness” to seep into his otherwise Ken-Loach-esque style. Occasionally, an elliptic bit of editing upends the documentary realism, as if Donald Cammell had got his hands on the footage. Adrian Wagner’s sparse atonal score manages to be upsetting in ways I’d need a degree in music theory to describe effectively.

Mainly, though, it’s the wrongness of how the characters behave and interact that makes Eclipse so squirmily compelling. Giles doesn’t seem that bothered by his father’s death. Or that bothered about prancing around the bathroom naked (child nudity isn’t unknown in art cinema – I’m looking at you, Peter Greenaway – but it’s an uncomfortable aesthetic choice and I’d argue the hell out of anyone prepared to make a case for it). Or that bothered about his mother keeping a fifth of gin in the bathroom cabinet. Just as Cleo herself, a wannabe artist, isn’t bothered about displaying in the living room she shares with her prepubescent son a life-sized canvas of her dead husband in the nude.

For a film in which very little happens, it’s impossible to tear your eyes from the screen. At least until it all becomes so intense that you need a break. I watched Eclipse over three nights, half an hour or so per sitting.

The Christmas Day sequence, which occupies the lion’s share of the running time, is one of the most excruciating expanses of cinematic space that I’ve ever navigated. Two set pieces – one involving the Christmas turkey, the other Giles’s train set – build to extremes of existential terror, the former chiming with David Lynch’s Eraserhead (released the same year), the latter something that wouldn’t be out of place in Michael Haneke’s filmography.

Without the sheer awfulness of Tom, Cleo and Giles’s Christmas Day, the understated, reflective Boxing Day scene, which segues from revelation to coda within the space of the closing few minutes, arguably wouldn’t work. As it is, the final scene tethers itself to the film entire on the wispiest of threads, a hair’s-breadth cut to the concluding image only just sealing the deal.

Eclipse is a fascinating one-off. It’s Simon Perry’s only outing as either writer or director (his decades-long career in cinema was as producer) and yet his script is a perfectly honed exercise in nuance and all of his directorial choices are spot on. It’s Gavin Wallace’s only acting credit, never mind that his performance puts most child actors in the shade. And to the best of my knowledge, it’s the only one of Nicholas Wollaston’s books that has been adapted for the screen. It works variously as psychological horror, a study in possession, and a remarkably sanguine ghost story. It’s not perfect – Conti’s performance wobbles (Hamilton, however, is mesmerising) – but it generates a quiet sense of perversity that heightens so subtly you don’t realise how powerful it is until it all but overwhelms you.

Lucy Bellingham