During a bracing Christmas Day walk around Nottingham’s picturesque Wollaton Park with my wife’s side of the family, I gave brief thought to the January editorial for CHAINLINK and failed to come up with any ideas. Later in the day, preparing the Christmas meal at my mother’s home in a sleepy Lincolnshire village, I gave it a bit more thought with the same zero result of ideas; I shrugged and poured myself a glass of wine. Driving back to Nottingham on Boxing Day, the same think-about-it/come-up-with-nothing scenario played out. I spent the afternoon finishing a review and editing a couple of contributions and put the editorial off for another day.

On the 27th, with a New Year’s mini-break imminent and opportunities to work on the editorial diminishing, I brainstormed. A round up of the year’s literary high points? I struggled to find any, beyond self and Shaun starting CHAINLINK. A round up of the year’s literary low points? I didn’t fancy going over the old ground of The Salt Path and the Len Pennie bad review/plagiarism accusations malarkey again. Something about writers who were born on New Year’s Day? I came up with E.M. Forster, J.D. Salinger and Douglas Kennedy but couldn’t find any commonality beyond shared birthdays. General thoughts on the state of the arts and predictions for the coming year? Exactly the kind of self-important noodling that I can’t stand to read, let alone have any interest in writing.

Finally, with a gnawing sense of self-loathing akin to visiting a prostitute, reading a Dan Brown novel or voting Tory*, I called up ChatGPT and prompted it thusly: “I need a New Year’s editorial for a literary journal.” It came back with eight paragraphs. Churned them out right in front of me. Took about 2.5 seconds.

Read it and weep:

Editorial: At the Threshold

Every new year arrives like a margin—white, narrow, and quietly demanding something be written into it. We step across its line carrying what we have saved and what we could not set down: unfinished sentences, half-learned lessons, griefs without endings, hopes without names. Literature, more than resolutions or calendars, understands this crossing. It has always been the art of standing at thresholds.

This issue is shaped by that pause between what has been and what might be. Not because the past year can be neatly summarized, or because the coming one can be predicted, but because writing gives us a way to hold uncertainty without trying to conquer it. In stories, poems, and essays, we rehearse change. We test new voices. We listen more carefully.

The new year often arrives under pressure to be new—new selves, new answers, new certainty. Yet literature reminds us that renewal does not require erasure. What endures matters just as much as what begins. The work collected here does not rush to declare conclusions. Instead, it lingers: with memory, with fracture, with the slow work of noticing. These pieces trust that attention itself is a form of hope.

Across these pages, you will find writing that resists easy optimism but also refuses despair. There are moments of quiet defiance, of tenderness, of sharp humor. There are voices reaching backward and forward at once, interrogating inheritance, language, and the fragile architecture of belief. Together, they suggest that the future is not a blank page so much as a palimpsest—written over, revised, and written again.

A literary journal is a communal act. Every issue is shaped not only by its contributors, but by its readers, editors, and the conversations that surround it. In a time when speed often replaces depth, choosing to read slowly is itself a radical gesture. To write slowly—to question one’s own certainty, to stay with discomfort, to listen for what is not immediately legible—is even more so.

As editors, we do not see this issue as a declaration of where literature must go, but as an invitation. An invitation to remain curious. To read generously. To allow language to surprise us again. The new year does not ask us to be finished or fixed. It asks only that we continue.

If there is a unifying thread here, it is this: beginnings are rarely clean, and endings are rarely complete. What matters is the willingness to speak anyway, to imagine anyway, to make room for voices that complicate the story we tell ourselves about who we are and where we are headed.

We are grateful to the writers who trusted us with their work, and to the readers who will meet it with open attention. May this issue keep you company at the edge of the year. May it remind you that language is still alive, still restless, still capable of lighting a path—however briefly—into what comes next.

There’s been a lot of commentary and controversy around ChatGPT, with many people wondering if it will render authors redundant. Having read the bollocks it produced at my request – cliched, soulless and fraught with fundamental misunderstandings (it doesn’t get what a margin is, for example) – I don’t think we need to worry. Well, maybe teachers and examiners who have to grade the work of students who have used ChatGPT as a cheat. But for those of us who apply the hard-won and constantly honed craftsmanship of writing to the raw material of human existence? I think we’re safe.

The reason I think we’re safe is that ChatGPT has never had a family Christmas, or a Christmas alone; never taken a walk on a frosty day round Wollaton Park or Hyde Park or Central Park; never seen a sunrise or a sunset; never got up at the crack of dawn to drive a truck or a bus or put in a shift at a hospital; never cared for a friend or a partner or a relative; never fallen in (or out of) love; never burned with anger or indignation; never roared along with the crowd at a sporting fixture or a rock concert; never disenchantedly torn up a losing betting slip or smugly pocketed the proceeds of a winning one; never slept in silk sheets or a holding cell; never thrown a punch or caught a lucky break.

So thanks but no thanks, ChatGPT. So long, AI, it’s been indifferent to know you. I’m filing this copy, then looking forward to the New Year’s Eve celebrations. I’ll take Auld Lang Syne, toasts with strangers, glasses clinked and quaffed and spilled; I’ll take the hangover and the depleted wallet; I’ll take the gloriously messy business of being human as the old year segues into the new, writer’s block or not.

*Full disclosure, I’ve only ever done one of these things, I bitterly regret it, and the film version wasn’t that much better either.

Neil Fulwood

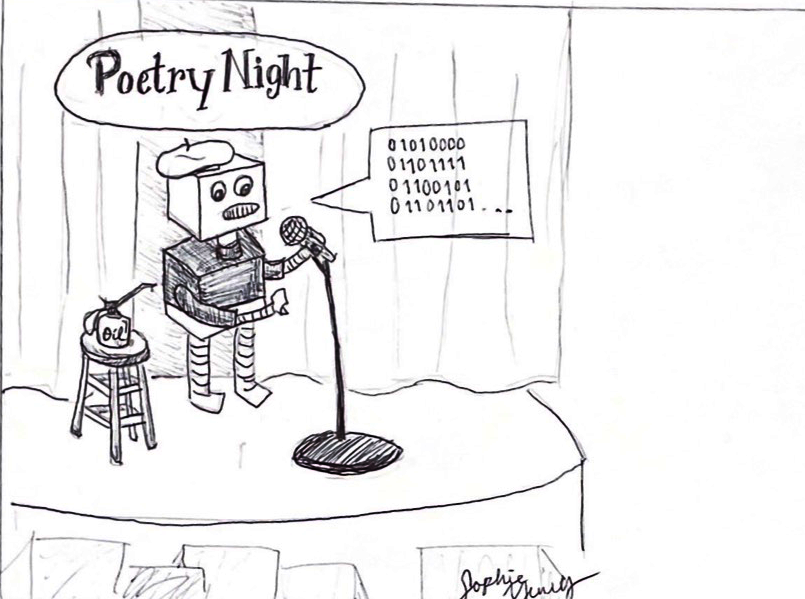

Cartoon Illustration: Sophie Young

The binary code above when decoded spells POEM