Cassandra Peterson has had quite the life. Bullying mother. Rough diamond father. Traumatic childhood accident (pan; boiling water). Socially awkward. Suddenly voluptuous. Go-go dancer in her mid-teens. Showgirl while still a good few years off being able to buy a drink legally. Self-styled “virgin groupie”. Accidental tourist, grand-touring Europe on a wing, a prayer, a hustle and zero budget. Extra in a Fellini opus. Actress on the make at the low-brow, low-budget yet still highly pressurised end of the American entertainment industry. Ensemble performer in touring productions. Party girl with a moral compass. Survivor of sexual harassment and abuse. Witness to a Hollywood murder. Resident of an honest-to-goodness haunted house. Animal rights activist.

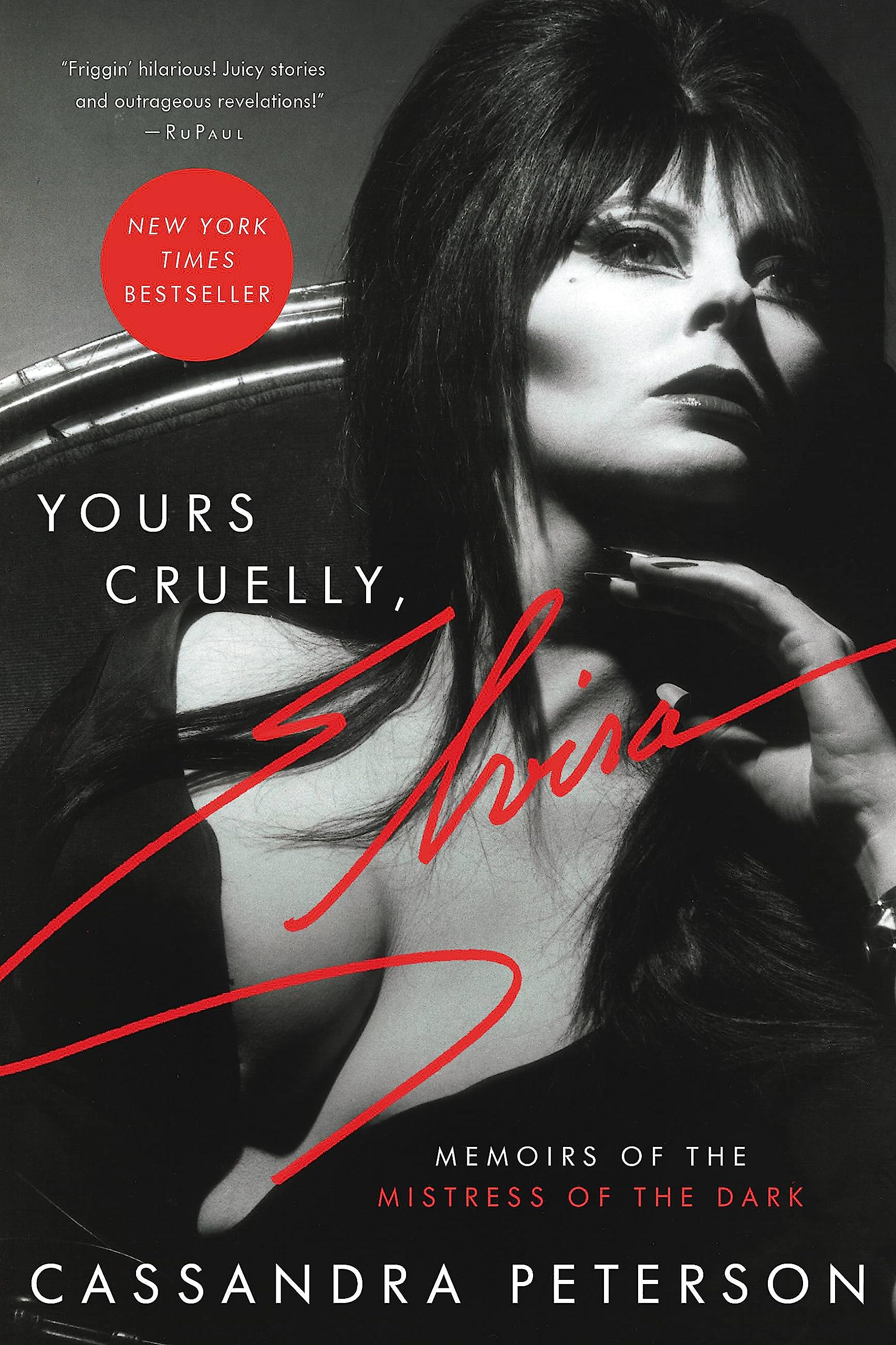

Oh, and she’s also the irrepressible personality behind Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, the mondo movie hostess turned movie star turned comic book icon turned Coors beer figurehead (never has such vampish allure been yoked to such abject swill) turned reality TV host (albeit short lived) turned sitcom protagonist (only for the entire series to remain unscreened due to some needledick executive who took umbrage at the degree of cleavage on display).

Peterson’s memoir is a real underdog story. Pawed at, patronised and passed over by priapic execs and casting couch horndogs, Peterson had almost reached her self-imposed make-it-by-thirty or give up and get a day job deadline when she landed the Elvira gig. Originally conceived as a reboot of the Vampira brand embodied by Maila Nurmi, and for which Nurmi would have received royalties, the show was almost deep-sixed after a volte face by Nurmi on the first day of shooting. An on-the-spot decision to simply rename the character as Elvira saved the day, making Peterson famous but putting her in the vengeful Nurmi’s sights for years afterwards.

Much of the memoir documents the downside of fame: the souring of her relationship with her husband/manager, the interference of TV and studio producers, and the elusiveness of financial stability (lawyers’ fees in fending off Nurmi; the haunted house as money pit; a ruinous divorce). Potential new directions for the Elvira brand are thwarted. Accidents plague her. Family members succumb to addiction or terminal illness. The AIDS epidemic cuts a swathe through her friends in the gay community.

All of this could have made for an endurance-course of a reading experience, but Peterson’s ready wit and indefatigable optimism bubble away throughout. Her prose style is zippy and unpretentious. One or two sections might have benefitted from a firmer editorial hand, but that’s a minor quibble. Peterson credits Stephen King’s On Writing as the book that gave her the confidence for her own literary endeavours, and as a lifelong King fan that just gives me another reason to like the guy.

Speaking of likeability, Peterson’s infectious personality is incandescent. Working on the hypothesis that there is no greater metric for one’s enjoyment of a work of autobiography than turning the last page and musing that one would really like to go for a beer with its subject and just luxuriate in their company and conversation, then Yours Cruelly, Elvira is one of the best.

Neil Fulwood

Leave a Reply