“One day he’ll be a famous conductor!” said Molly Drake as her five year old son, Nick, waved in time with the music on his nursery wind-up gramophone. If only.

As history transpired, Nick Drake (1948-1974) became one of the greatest and most influential singer/songwriters in the history of music – and one of the most tragic.

Born into a well-to-do post-colonial family and raised in the stunningly beautiful Warwickshire village of Tanworth-in-Arden, Drake – taking after his creative mother, who was an accomplished pianist and singer in her own right – showed prodigious musical talent at an early age, taking up the piano, the clarinet and – most propitiously – the guitar. He began composing his own tunes as a young child and while an English Literature student at Cambridge, wrote and recorded the now iconic series of songs that comprise his 1969 debut album, Five Leaves Left. By which time he was still only 20.

Everything seemed to be going well for Drake at this stage: Following a private recital for the Rolling Stones, he was then spotted while guesting at a London ‘happening’ by legendary producer Joe Boyd of Island Records – then considered the coolest label on the planet. Stunned by the haunting quality of Drake’s songs, his eerie, fragile husky voice and intricate open tuned, quasi-orchestral guitar playing, Boyd promptly signed Drake to Island and during the spring of 1968 Five Leaves Left was recorded but not released until August 1969.

Standing distinctly apart from the usual raucous Americanized shouting and screaming of most pop artists and performers of his and our own times, Drake’s quiet songs seem to come from a much older period – hailing back to the English Folk Tradition that goes via Vaughan Williams to the ancient troubadours of medieval legend, replete with their cryptic Occitan lyrics. Indeed, I would aver that the song cycle that constitutes Five Leaves Left is the finest of its kind since Schubert’s Winterreise. Drake’s own musical tastes certainly leaned towards the Classical, with the works of Bach, Delius and Ravel among his personal favourites. His literary studies too played their part, admiring as he did the works of Blake, Keats, Shelley and Yeats with their Gothic fusion of existential power and prophecy.

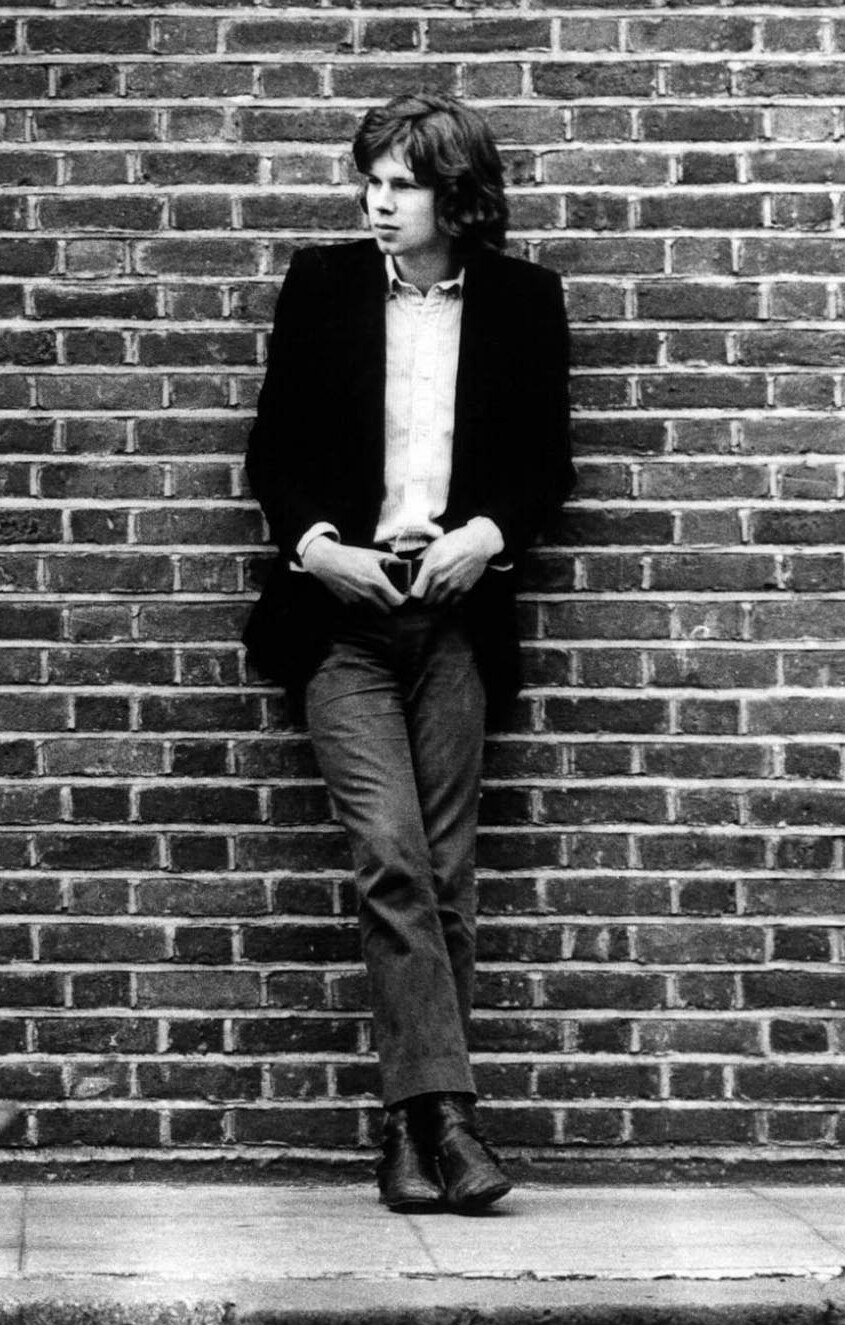

By 1970, Drake should have been a superstar. Along with his remarkable musical talent, Drake was blessed with a spectral, androgynous physical beauty which put many in mind of a great Romantic poet. Those who met him all attest to his tall stature, mystical charisma, quiet exquisite manner and wry sense of humour. Drake was also very shy, introverted and outside music, he found it difficult to communicate with others. This last characteristic, along with his hitherto comfortable and protected childhood, soon became a serious handicap when, led to believe by Boyd that Five Leaves Left would be a huge commercial success, he abandoned his studies at Cambridge and moved to London to prepare his second album, Bryter Layter.

Alas, then as now, the streets of London are paved not with gold but with miserable bedsits while record companies similarly fail to deliver on their deceptive promises of fame and fortune.

While Five Leaves Left was recorded with painstaking care, Island Records’ actual marketing of both Drake and the album was disastrous. Delayed by months due to post production incompetence, when Five Leaves Left finally appeared there were serious printing and spelling errors across the inlay sleeve (songs in the wrong order, omitted verses etc.) along with misplaced credits and recording information. Similar issues surrounded the release of Drake’s second album, Bryter Layter. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

To make matters worse, Drake was mismanaged when it came to personal promotion. Sent out on the road by Boyd to promote the albums at venues as varied as the Royal Festival Hall, college campuses and working men’s clubs, Drake, previously used to singing at small intellectual gatherings at Cambridge or Hampstead, was given no professional guidance or preparation about how to actually perform to larger and more varied audiences. Nor did he travel with a road or stage manager who could have helped him cope with the inevitable talkers, hecklers and sometimes hooligan elements that form the occupational hazards for the travelling entertainer. The naturally shy Drake found most of these gigs traumatic experiences and, unable to banter with usually noisy drunken audiences who weren’t interested in his quiet songs, would sometimes leave the stage mid-performance.

Thus began a vicious and ultimately tragic circle for Drake: Needing to promote both Five Leaves Left and Bryter Layter by way of public performance was essential in order to secure decent sales for the albums but their poor initial take-up shattered Drake’s delicate self-confidence which in turn led to his withdrawal from the concert scene. This left only the option for studio performances for both radio and television. However, apart from a recording session for the John Peel show and a one-off appearance on the long-forgotten (and sadly wiped) Manchester based music TV programme, ‘Octopus’ (which would have constituted the only film or video footage of Drake as an adult) nothing came of these initiatives either.

By the time of his third album, Pink Moon, Drake was a shadow of his former self. Seemingly abandoned by Boyd who had left behind his Witchseason Productions company deal with Island Records whereby his artists’ records were released, to return to America. Already showing early symptoms of psychosis, Drake left London in the autumn of 1971 to return to the Georgian manor comforts of his parental home in Tanworth-in-Arden. His last three years comprised a distressing descent into depression, nervous breakdown, schizophrenia and finally suicide at the age of 26.

As so often happens in these cases, within a few short years of his untimely death the Cult of Drake began, with his songs appearing on television commercials, films and TV dramas. Then of course, came their reissue on CD, the internet and the download – all making millions in the process.

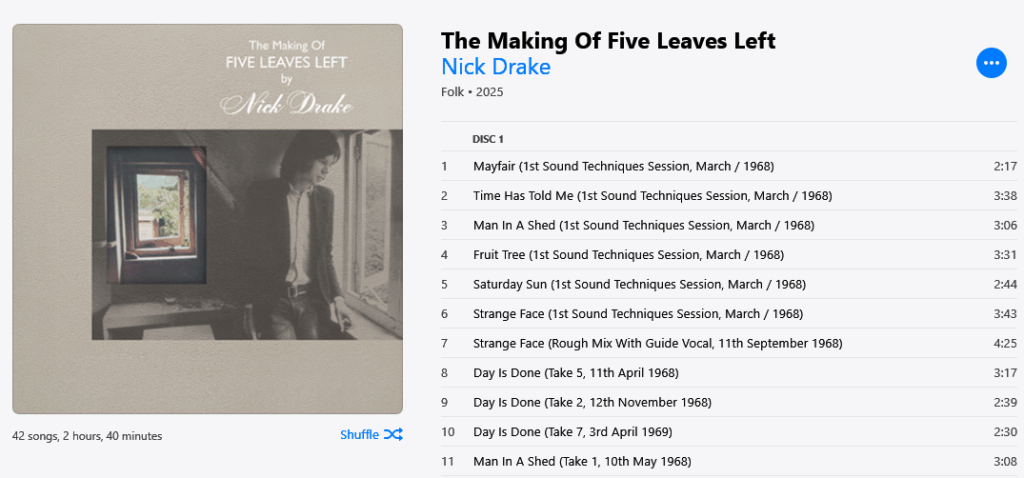

Now, more than fifty years after his death, Universal Music has released a lavishly appointed 4LP/4CD Collector’s edition set of Five Leaves Left, which has been given a level of remastering and retro repackaging more in keeping with recent classical commemorative special editions of the Britten War Requiem and the Solti ‘Ring’ cycle.

All very complimentary. But I for one couldn’t help feeling slightly sick at the sight of certain members of Drake’s professional circle who are still very much alive today, photographed and videoed sitting happily on a boat on the Thames as they each hold a copy of the new Five Leaves Left edition as part of Universal’s extensive official promotion campaign. There’s a dedicated web and Facebook page to help sell the set and there’s even an official Nick Drake Store where you can buy it along with T-shirts and tote bags emblazed with artwork from Drake’s original three completed albums.

Indeed, there is one person there in particular who will no doubt do very nicely out of this. The one person upon whom Drake depended for his artistic success; the one person who callously abandoned him, cut off his advance royalty payments and left the greatest artist ever to grace his label to a foreshortened life of despair, penury and obscurity. How short memories are. Still, without him I suppose Drake’s recorded legacy, small as it is, may never have existed in the first place so feelings – at least on my part – remain decidedly mixed on the matter.

Nick Drake never sought stardom or limelight in the same way as his posturing contemporaries Bolan, Bowie and Mercury did. His existential songs were meant to bring comfort and reassurance to those in need. – which is one reason why they have become so popular today.

Not long before his death (some say by accident, others by design) by way of an overdose of anti-depressants in the early hours of November 25th 1974, Drake declared to his mother that he had “failed in everything I’ve tried to do” – in other words he felt his music had not reached people, especially young people, who had the same problems as himself.

Resting beneath a great oak tree in a green valley in deepest middle England, Nick Drake can and has been assured that his music is in fact a great and continuing success which will remain as timeless and priceless as any of the music of the great composers he himself so greatly admired. Remembered for more than a while.

Robert Kenchington

Leave a Reply