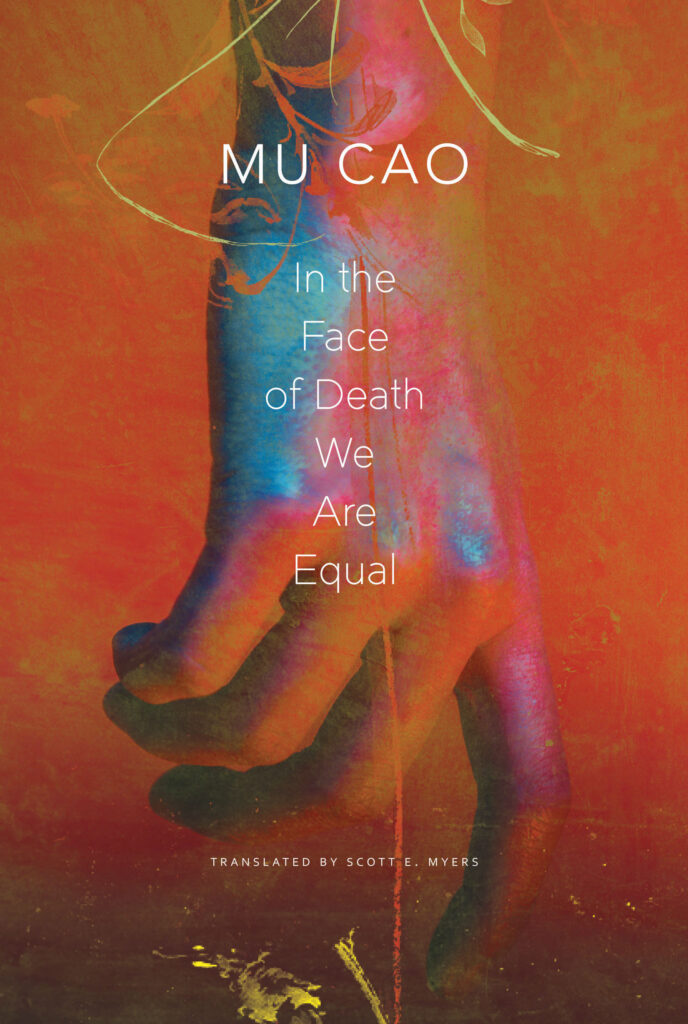

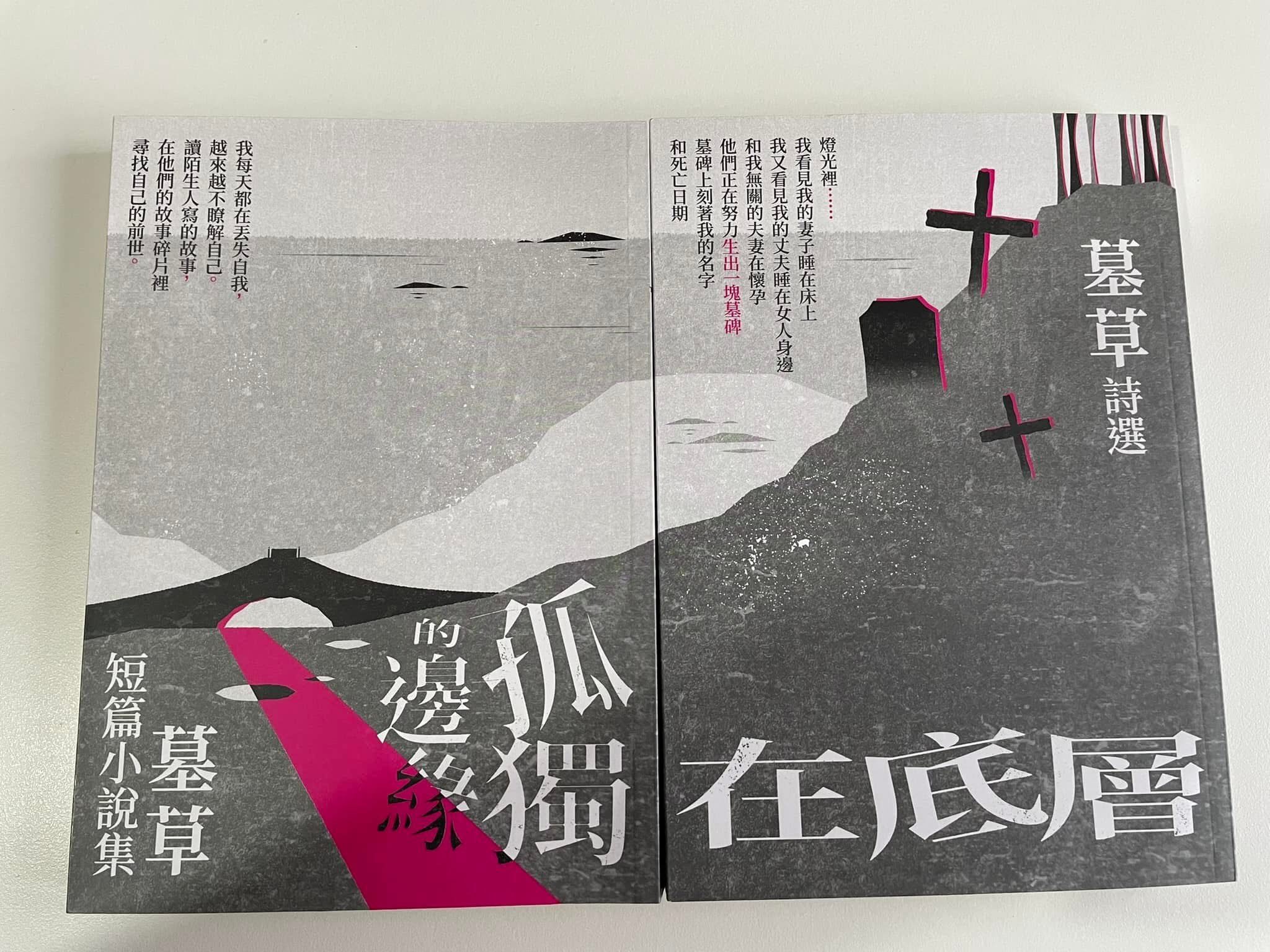

For more than two decades, working-class queer Chinese Mu Cao 墓草 (b.1974, Henan, China) has been a unique voice in Chinese literature and global queer literature. Often referred to as a ‘folk poet’ and ‘a voice from the bottom of Chinese society’, his poems celebrate queer desire and migrant worker experience. A high school drop-out, Mu Cao taught himself poetry and fiction by reading extensively. Lacking access to a stable income and a permanent residence, he drifted from one city to another, working on poorly paid odd jobs and living on the fringe of Chinese society. Unable to publish in official literary journals or find a publisher due to China’s censorship of LGBTQ+ content, he takes to self-publishing and publishing online. No obstacle has stopped him from writing. Mu Cao has published six poetry collections and four works of fiction, mostly in Chinese, since 1998. His novel Qi’er 弃儿 (In the Face of Death We Are Equal), translated into English by Scott Meyers, was published by Seagull Press in 2019. His latest publications in Chinese include short story collection Gudu de bianyuan 孤独的边缘 (The Lonely Fringe) and poetry collection Zai diceng 在底层 (On the Underside), both published by Showwe Press in Taipei in 2023. There has not been a translation of Mu Cao’s poetry collection, in English or another language, yet.

Mu Cao’s poetry should be understood in three interrelated contexts: First, the living and working conditions of migrant workers in China, which is usually the subject matter of Mu Cao’s poetry. China’s fast economic growth and its place in the global economic chain rely on a constant supply of cheap labour making affordable goods. This necessitates large-scale rural to urban migration within China, often from the countryside to coastal cities where manufacturing industries are located. In the cities, these migrant workers are often treated as second-class citizens, heavily exploited in sweat factories and having no resource to decent social welfare provision. Second, the invisibility of LGBTQ culture in China. Although homosexuality is, strictly speaking, not illegal in contemporary China, queer culture is often banned from media and cultural representation, and LGBTQ public events are frequently cancelled under the government pressure. China’s LGBTQ community appears largely young, urban and middle-class, and people from rural and working-class backgrounds are often marginalised. Mu Cao’s poetry is a rare example of queer poems depicting the working-class queer life. Third, China’s unofficial and often underground publishing culture, which has made the production and dissemination of Mu Cao’s poetry possible. Although queer poetry and migrant workers’ poetry have no place in China’s literary establishment, a vibrant underground, self-publishing culture since the 1990s enables Mu Cao to publish his own pamphlets and books. The internet and social media have also facilitated the dissemination of his poetry, but they have also subjected his poetry to greater surveillance and censorship. Despite this, many of his poems have survived, and a small portion has been translated into several languages. All the three contexts contributed to the subject matter, style and aesthetics of Mu Cao’s poetry.

Mu Cao had not received much critical attention until recently. In 2015, Mu Cao was awarded the Underground Poetry Award by Freebooters (江湖), one of the most radical unofficial poetry journals in China. In 2024, Mu Cao received a Prince Claus Impact Award from the Netherlands for ‘promote[ing] queer expression through bold, dark, and expressive poetry,’ making him the only writer from around the world that year to receive the prestigious award. The Prince Claus Impact Award jury honours Mu Cao with the following words:

For his unique literary voice, characterised by its raw and fierce qualities, fearlessly delving into taboo subjects with rare expressiveness; For shedding light in unprecedented ways on the realities of marginalised communities in China; For his contribution to queer culture in China and asserting queerness beyond Western boundaries; For his commitment to fighting against social hierarchies, emphasising the importance of self-expression and agency.

In an official video interview made for the award, Mu Cao explains the importance of writing for himself:

I used to be a farmer. I worked as a street vendor, cleaner, mover, warehouse worker, factory worker, hotel attendant, restaurant waiter, caregiver, web editor and more. I’m a wanderer in the city. I have been working for over thirty years, with no social security, no property. But I like writing. Writing is the belief that keeps me alive.

Mu Cao’s poetry is known for its dark and pessimistic tones, his obsession with the death imagery and his use of black humour and surrealism. The pen name ‘Mu Cao’ literally means ‘grass on the tomb’. The name vividly captures his view of society and his overwhelming sense of pessimism, albeit also with a faint touch of hope. I have chosen eight poems to represent Mu Cao’s oeuvre from the past decade. ‘the despair you’ve never felt’ is a poem about Mu Cao’s alienated relationship with his parents. He subverts the traditional, heteronormative family kinship with twisted queer humour. ‘oh, spring’ depicts the memory of a past lover. ‘shangcheng street’ is a piece of social satire using black humour to expose the hierarchies and injustices of society. The next four poems (‘work’, ‘light’, ‘condemned building’ and ‘sleep under cctv cameras’) fall into the umbrella of what literary historian Maghiel van Crevel calls ‘battler poetry’ (打工诗歌), poems written by migrant workers depicting their life and work. These poems are short, quiet, matter of fact even, but they serve as important documents of the harsh working and living conditions in China’s ‘world factory’ under exploitative global capitalism. The last poem ‘tomb-sweeping festival’ is signature of Mu Cao’s use of dark imagery to evoke death and despair.

Hongwei Bao

Read Hongwei Bao’s translations of Mu Cao’s poems HERE:

Leave a Reply