Effective oppositional spaces are rapidly disappearing. Democratic process is blocked by inequality, authoritarianism, deceit and a narrow ideological consensus. Constitutional and legal constraints on power, within and between nation states have no answer to violence, dishonesty and lawlessness. The Fourth Estate is browbeaten and cowed. Traditional forms of political participation (joining political parties, leaving political parties, voting, not voting, letter-writing, demonstrating, collecting signatures, etc) make no difference. Peaceful protest is criminalised.

What then – if anything – can writers do to oppose the different but overlapping ideologies of, say, Trump, Farage and Starmer? How do you ridicule the ridiculous, or monster a monster? Why bother to try to ‘speak truth to power’ when nobody in power is listening? Is it possible to use language to talk about the degradation of language (‘self-defence’, ‘terrorism’, ‘democracy’, ‘incursion’, ‘anti-Semitism’, ‘change’, ‘rules-based’, ‘an island of strangers’)? How can writers seriously engage with contemporary issues when so much public discourse is reduced to blatant lies, implausible denials and dog-whistle politics? In particular, how, in a noisy world, do poets resist the temptations of silence?

On the one hand, poetry publishing is economically insignificant. British poets are politically silent, easily bought and quickly marginalised. The poetry scene is atomised and isolated from British society, its inaccessibility hardly disguised by protestations of diversity and inclusion. Conversations about poetry are reduced to the language of hyperbolic press-releases promoting award-winning poets, corporate prizes and celebrity book-festivals.

On the other hand, poetry is primarily a mass and amateur activity located outside the ideological apparatus of the state. It can mobilise popular feeling, bear witness, express dissent, educate desire, organise opposition and isolate the enemy.

Having no culture of its own, the enemy does not understand – and is therefore afraid of – the democratic potential of any art. Poetry especially. The attacks by Keir Starmer, Kemi Badenoch, Lisa Nandy and Wes Streeting on Irish rappers Kneecap and punk rappers Bob Vylan during this year’s Glastonbury Festival may have helped to distract attention from the news that the IDF had killed over 600 Palestinians in the past few weeks at food distribution centres (at least 59 were killed on the day of Bob Vylan’s performance). But they have hardly dented support for the Palestinian cause among a public who appear to have concluded that they would rather belong to Palestine Action than its much bigger rival, Palestine Inaction. And it makes those in power look hopelessly out of touch; compare the chants of ‘Oh Jeremy Corbyn’ at Glastonbury in 2017 with this year’s refrain of ‘Fuck Keir Starmer’.

Not for the first time, a contemporary political issue has been turned into a morally loaded debate about poetry and a diversionary attempt to police language and cultural expression. Consider the Tory attacks on the ‘cascade of expletives’ in Tony Harrison’s V during the Thatcher years, or the prosecution of Joolz for using ‘words… likely to cause alarm, harassment or distress’ at an anti-Fascist poetry reading in Leeds in the early 1990s. Much of the tabloid coverage of the disturbances in 2011 in British cities following the shooting of Mark Duggan by the Metropolitan Police, was not about race or poverty or policing but about poetry, specifically what the ludicrous David Starkey called ‘violent, destructive and nihilistic black culture’ and the ‘fashionable’ and ‘false’ language of Rap, Dub and Hip Hop poetry.

But there is no such thing as ‘false’ language. Attempts at policing and controlling language, including the language of poetry, are always self-defeating. The world may be full of loud-mouthed liars and credulous listeners. But language is an exchange of meaning and understanding or it is not language. And poetry is a means of communication, or it is not poetry. Poetry is not a monologue or a soliloquy. The power of poetry is located in the relationship between speaker and listener. It is a social act. Poetry – saying in memorable ways what needs to be said, remembering what needs to be remembered, celebrating what needs to be celebrated, condemning what needs to be condemned – is essentially a shared, collective, public activity.

Until the emergence of mass-literate societies a hundred and fifty years ago most poetry was spoken and shared, listened to, learned and shared again. The distinction between speaker and listener was blurred by the mnemonics of rhythm, metre and rhyme, enabling listeners to join in a poem’s music. While this may be forgotten on the poetry-prize-winning circuit, it is still understood by those who have been historically excluded from written language by the forces of empire and slavery and class (it is always the poorest people who speak the most languages). The shared making of a poem in performance is still an act of remembering and a kind of imaginative anticipation, both memory and dream.

The Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish once said although he had two languages, ‘I forget which of them I dream in.’ If the twenty-first century is characterised by exile, emigration and violent displacement, what are the implications for poets who must leave their native languages behind? And what language do they dream in?

In the past forty years, when so much contemporary British poetry was dying of boredom, Black British poets kick-started new kinds of poetry by importing African, African-American, Afro-Caribbean and Indian sub-continent oral, performance and musical traditions and by insisting on the ‘mean’ language of everyday living.

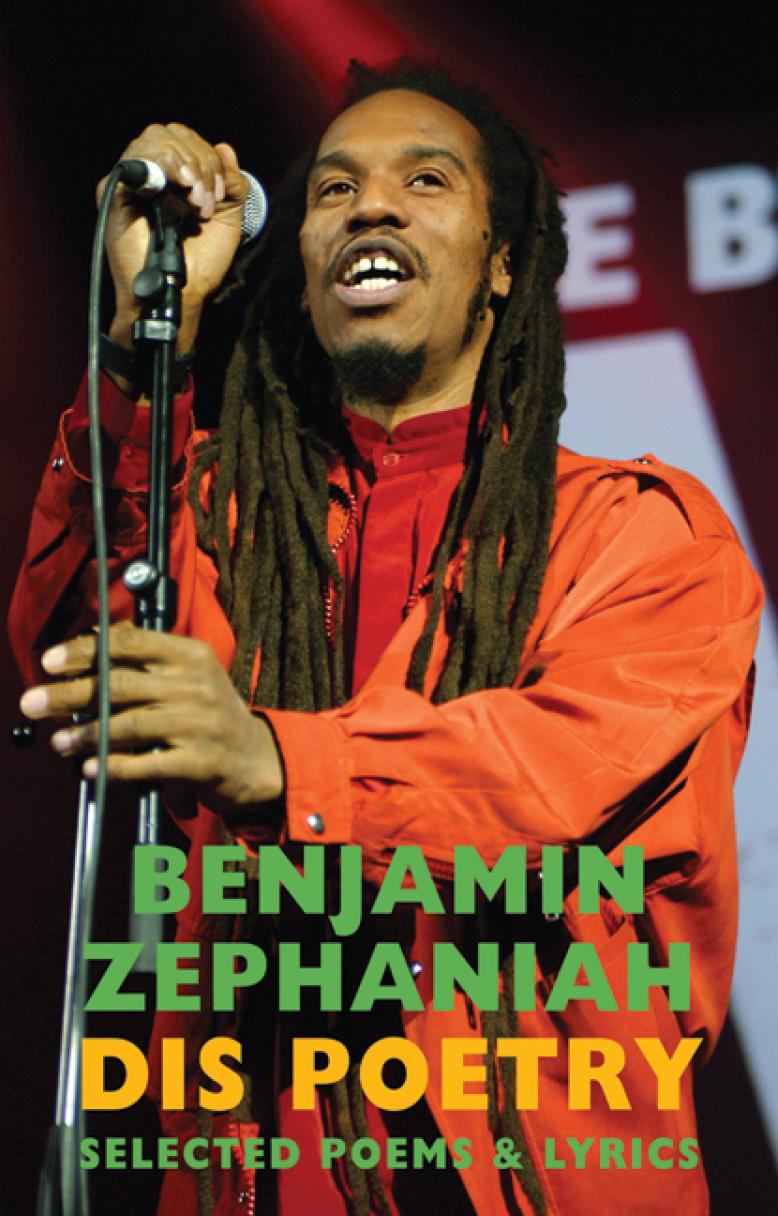

No poet exemplifies this better than the late Benjamin Zephaniah, whose Dis Poetry: Selected Poems and Lyrics is just published by Bloodaxe Books. It’s a huge book, in every sense. 300 pages of poems from The Dread Affair (1985), City Psalms (1996), Propa Propaganda (1996) and Too Black, Too Strong (2001), plus a number of unpublished poems and lyrics from Zephaniah’s albums. But huge also in its ambition and its linguistic range.

Put together within the covers of a single book, Zephaniah’s work adds up to something really extraordinary. Although there aren’t that many individually great poems here, they run together as though the book is really one long poem, or rather several hundred attempts at writing the same poem. I can’t think of many other British poets whose work reads like this – DH Lawrence, Adrian Mitchell, John Clare, Michael Rosen perhaps.

There is something about Zephaniah’s poems which makes you forget that they were ever ‘composed’. The language is fiercely ordinary, conversational and direct, as in ‘The Death of Joy Gardner’:

‘They put a leather belt around her

13 feet of tape and bound her

Handcuffs to secure her

And only God knows what else,

She’s illegal, so deport her

Said the Empire that brought her

She died,

Nobody killed her

And she never killed herself.’

Elsewhere, Zephaniah slips in and out of idiomatic and demotic speech, phonetic spelling and the rhythms, repetitions, echoes, pauses, compressions and rhymes that made him such a brilliant performer. This is a defiantly bilingual poetry:

‘Who will translate

Dis stuff?

Who can decipher

De dread chant

Dat cum fram

De body

An soul

Dubwise?

… Sometimes I wanda

Who will translate

Dis fe de Inglish?’

But self-mocking too (‘Two dozen Babylon dem a follow me / As me driving in me dreadlocks car’). The effect is not a narrowing of address, as in so much regional dialect poetry, but a widening of audience. Zephaniah is speaking to everyone. And everyone can listen if they want to. He may have been, as he put it, ‘an angry, illiterate, uneducated, ex-hustler, rebellious Rastafarian’ but he was also ‘a poet who won’t stay silent’:

‘So they put me in the BBC and they put me on Question Time and stuff like this

As if, I’m kinda willing to play that game

I mean I will go on and talk

But deep down

I’m a revolutionary…

So when the people speak you must listen

They rioted from Junction to Tottenham to Brixton

Cause police turned Mark Duggan into a victim

And the struggle’s bigger than the one that we are living in

Israel has made Palestine a prison…’

He was wonderfully unforgiving of those who would own and control Black experience –liberals preening themselves with the wisdom of hindsight (‘Who Dun It?’), the ‘Race Industry’ (‘They take our sufferings and earn a salary’) and Black poets who allow themselves to be ‘Bought and Sold’ (he very publicly refused Blair’s offer of an OBE):

‘Smart big awards and prize money

Is killing off black poetry…

The empire strikes back and waves,

Tamed warriors bow on parades,

When they have done what they’ve been told

They get their OBEs…

we give these awards meaning

But we end up with no voice.’

Benjamin Zephaniah had a voice all right. And he knew that it didn’t belong exclusively to him. At a time when young would-be poets on Creative Writing MAs are busy looking for their individual ‘voice’, Zephaniah’s interchangeable use of ‘we’, ‘I’ and ‘you’ made his writing both distinctive and everyday. He wrote like a man talking. But not a man talking to himself. He always knew to whom and for whom he was talking. And why the conversation needed to happen:

‘If you live in the kitchen and can’t afford chicken

blame dem, not me.

And if the tax you pay is high and you’re living in the sky

blame dem, not me.

My unbringing resembles yours,

a life of toil, a life of chores.

So if you get upright and you want to fight,

fight dem.’

For Zephaniah, the experience of being Black gave him access much wider truths about class, race and community, and universal truths about being human – ‘when I say “Black” it means more than skin colour. I include Romany, Iraqi, Kurds, Palestinians… the battered White woman, the tree dwellers and the Irish…’

Among the recurring subjects of Dis Poetry are racist killings on British streets – specifically the murders of Rolan Adams, Akhtar Ali Baig, Mark Duggan, Stephen Lawrence, Michael Menson, Manish Patel, Ricky Reel – and the deaths in custody of Black men and women –Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas, Joy Gardner, Shiji Lapite, Alton Manning, Oscar Okoye, Colin Roach and Kenneth Severin:

‘I have stood for so many minutes of silence in my time.

I have stood many one minutes for

Blair Peach

Colin Roach

And

Akhtar Ali Baig,

And every time I stand for them

The silence kills me.

I have performed on stage for

Alton Manning

Now I stand in silence for Alton Manning.

One minute at a time, and every minute counts.

When I am standing still in the still silence

I always wonder if there is something

About the deaths of

Marcia Laws

Oscar Okoye

Or

Joy Gardner

That can wake this sleepy nation.

Are they too hot for cool Britannia?

When I stand in silence for Michael Menson

Manish Patel

Or

Ricky Reel

I am overwhelmed with honest militancy,

I’ve listened to the life stories of

Stephen Lawrence

Kenneth Severin

And

Shiji Lapite

And now I hear them crying for all of us’.

The US poet Tom McGrath once compared writing poetry to learning to swim or to skate on ice:

‘It’s not easy, but it can be done, if you want to do it. Maybe you won’t be able to skate farther than across the pond. [But] the language is there, all you’ve got to do is to – like the snake, get out of your skin (which is all the cliché and shit language that you’ve had) and be a born-again snake, or poet, or snake-poet, or whatever. Then it becomes a possibility. When Sitting Bull needed to write his death song, he just said it. Didn’t write it, it was there.’

Dis Poetry is Benjamin Zephaniah speaking, not his death song but his life song. It was far too short a life, but a long song, angry, funny, generous and utopian:

‘I see a time

When angry white men

Will sit down with angry black women

And talk about the weather,

Black employers will display notice-boards proclaiming.

“Me nu care wea yu come from yu know

So long as yu can do a good day’s work, dat cool wid me”…

I see thousands of muscular black men on Hampstead Heath

walking their poodles

And hundreds of black female Formula 1 drivers

Racing round Birmingham in pursuit of a truly British way of life.

I have a dream

That one day from all the churches of this land we will hear

the sound of that great old English spiritual,

Here we go, Here we go, Here we go…’

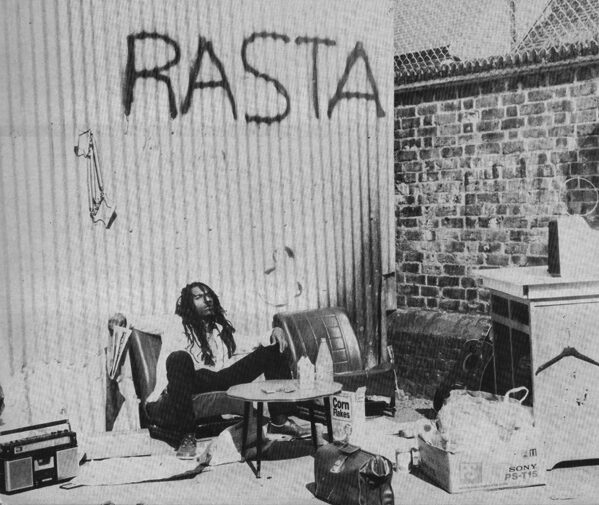

Now safely dead, Benjamin Zephaniah is of course a National Treasure, remembered fondly even by the Daily Mail as ‘the Peaky Blinders star’ and ‘world renowned poet. This was the newspaper that told us Keats, Shelley and Byron would be ‘turning in their graves’ when Zephaniah was invited to apply to be a visiting Fellow at Cambridge. Meanwhile, an editorial in the Sun asked, ‘would you let this man near your daughter?’ – ‘He is black. He is a Rastafarian. He has tasted approved schools and Borstals. And, oh yes, he is a poet.’ But of course, they were right to be afraid of Benjamin Zephaniah. He was a revolutionary poet. And a revolutionary:

‘Revolutionary minds don’t give a damn

Dem a work till revolution dawn

Revolutionary minds are rebellious

Revolutionary tongues say gwan

Revolutionary minds don’t give a damn…

Women shall not be property

When revolution come, come on, come on, come

And no-one shall be judged by the colour of their skin

When revolution come, come on, come on, come

The elders shall live in dignity

When revolution come, come on, come on, come

And we will control de lives we’re living

When revolution come, come on, come on, come.

Andy Croft

Andy Croft’s most recent book is Release the Sausages: Poems for Keir Starmer (Culture Matters).

Read a review here:

The book available here:

Leave a Reply